About the author

Page last updated by Dr Elaine Ryan

What is Anxiety?

If you’ve found this page because you’re looking for help with the different anxiety treatments available, I’ll walk you through what actually works — whether you’re thinking about coming to see me in my Dublin clinic, or you GP referred you for CBT, working together online from anywhere in Ireland, or exploring a self-paced course. The first step is understanding what anxiety is and how it shows up in your brain and body — because that helps you choose the right treatment for you.

Table of contents

- What is Anxiety?

- Anxiety Symptoms

- Where do you feel anxious?

- Your 3 brains

- Retrain Your Brain

- Find the root cause of your anxiety.

- Different Pathways to Anxiety

- In order to reverse your anxiety, you need to Retrain Your Brain®

- Types of Anxiety Disorders

- Cause of Anxiety: Understand the Factors

- How to Know if You Need Professional Help

- Anxiety Treatment Options with Dr Elaine Ryan Dublin

- The Science of CBT for Anxiety: How It Works

- Self Help

If this is the first time on my site, my name is Elaine and I am a Doctor of Psychology who has spent two decades helping people with anxiety disorders and have also had anxiety myself; panic disorder to be specific. As well as being able to help you, I know what you are doing through.

Retrain Your Brain®

If you would like my help.

All my materials are now online in my Retrain Your Brain program to unlearn anxiety. It’s very important to me that you find my course useful. If you do not, all my courses come with a 10 day money back guarantee.

Many people come to see a psychologist thinking they will just ‘talk’, but a key part of what I do is like detective work, breaking down what drives your anxiety, I don’t have a magic wand behind my style of working but I do have decades of experience using models that provide a structured framework that turns all your anxious thoughts and feelings into something you can understand with actionable steps to help you overcome it. All anxiety can be understood using scientific models and throughout this guide I shall show you how anxiety isn’t something that is just happening to you; it follows a pattern that you can interrupt and change.

Dr Elaine Ryan

Quick Check: Is Anxiety Really “Random”?

Even though anxiety often feels random, modern psychology and neuroscience show it follows a predictable cycle of

- a situation or trigger,

- anxious thoughts (“What if I mess up?”),

- emotional and physical reactions (racing heart, dread), and

- behaviours (avoidance, escape).

Recognising this cycle is a key step in learning to manage your anxiety and throughout this article I shall show you how it all fits together; understanding anxiety is like piecing together a puzzle.

Mini Exercise: Recall a recent time you felt anxious. What sparked it? What “doom” thought jumped into your mind? How did your body react? Did you do something—like cancel plans or leave early? Notice how each link led to the next.

We shall use your data later to show that anxiety often unfolds in four parts: a triggering situation, the thoughts that spark fear, the emotions that follow, and the bodily sensations that drive you to act or avoid. We can break each step down through something called a ‘chain analysis,’ showing that anxiety isn’t random, but rather a sequence we can interrupt. But first I need to explain normal anxiety, as not all anxiety needs to be treated.

Normal versus Clinical Anxiety

Normal (situational) anxiety is a temporary response to stressors like an interview or an exam, it occurs in response to a specific situation and then goes away. It becomes abnormal, or clinical anxiety, when it is excessive, persistent, and interferes with daily life and one of the first things that people notice, is that they feel different, their body feels different, and this is what I shall talk about now – the symptoms that you can experience when you get anxious.

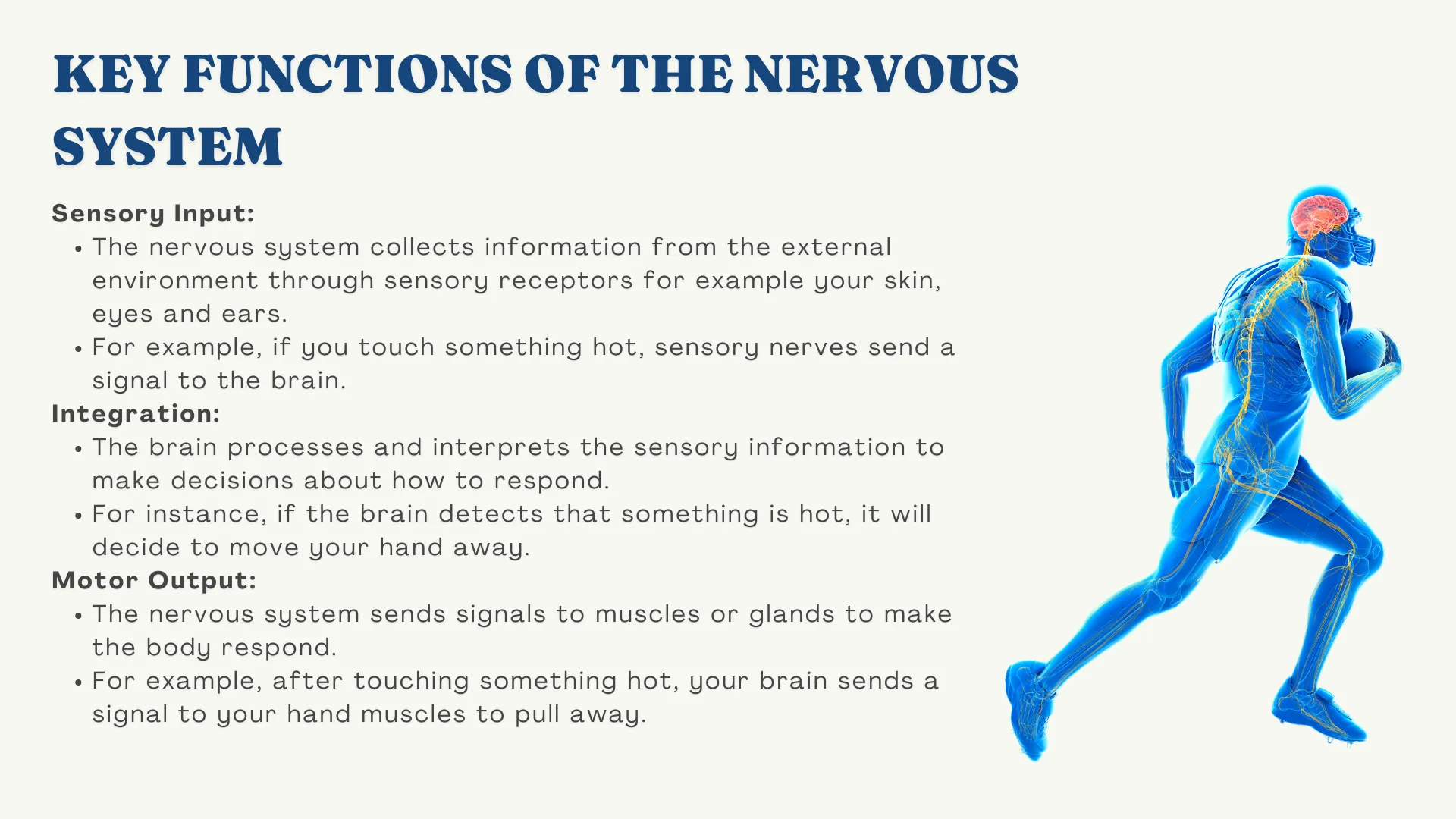

Anxiety is the response you get when your brain detects a ‘threat.’ Once a threat is detected, your stress response is activated, and it is this ‘stress response’ that gives you the uncomfortable feelings in your body, and causes your mind to race.

In order to understand what anxiety is, I find it useful to draw from evolutionary psychology as it allows me, and hopefully you, to see that anxiety is an adaptive response that should be useful, but our intelligence gets in the way. Let me explain.

In the very short video above, I start by showing you how your brain should respond when it detects a threat. Threat detected, brain gives you the energy to prepare for danger and you calm down when the threat has passed.

Those early humans who could detect ‘threats’ quickly and respond appropriately were more likely to survive, and therefore more likely to pass on their adaptive ‘threat detection system’ to their children.

As we evolved, we lost the threat from predators, but kept our threat detection system. It’s like we still have this primitive threat detection system, but are now using it to detect threats in the office, or wherever we happen to be. That might sound flippant, but it is extremely important you understand that it is the same stress response, that helps you stay alive, that gets activated in today’s modern world. But because you do not get the opportunity to burn it off by running; the physiology of it leaves you with the symptoms you are now seeking help for.

How does anxiety develop?

In primitive man, the stress response is activated once a threat (predator) is detected. The stress response gives him the energy to fight the predator or run away – hence why we talk about the fight or flight response.

Once he is out of harms way, his body calms down again. This quick burst of energy, in my mind is not anxiety, rather it is more akin to fear and this is an important difference, as I shall explain now.

Modern day man detects a threat, such as worrying about money and his stress response gets activated. He still gets this big burst of energy, but what he is now experiencing is anxiety, as opposed to fear.

Fear is where there is a real danger present ( a real threat ) and anxiety is where you are worried about a ‘threat’ that may occur in the future.

There is nothing physically wrong with you, the symptoms of panic and anxiety are harmless if experienced appropriately. I’m a doctor of psychology and have experienced both anxiety and panic. My purpose in telling you this, is to normalize your experience, as you may feel alone with what is happening. Anxiety, in one form or other, will be experienced by most of us at some stage. The problem is we do not speak about it – there is still stigma. I want to break down that stigma. In order to for me to ensure that you fully understand the symptoms that you are experiencing, I first need to explain your nervous system. It’s a bit long winded, but it is really important that you understand.

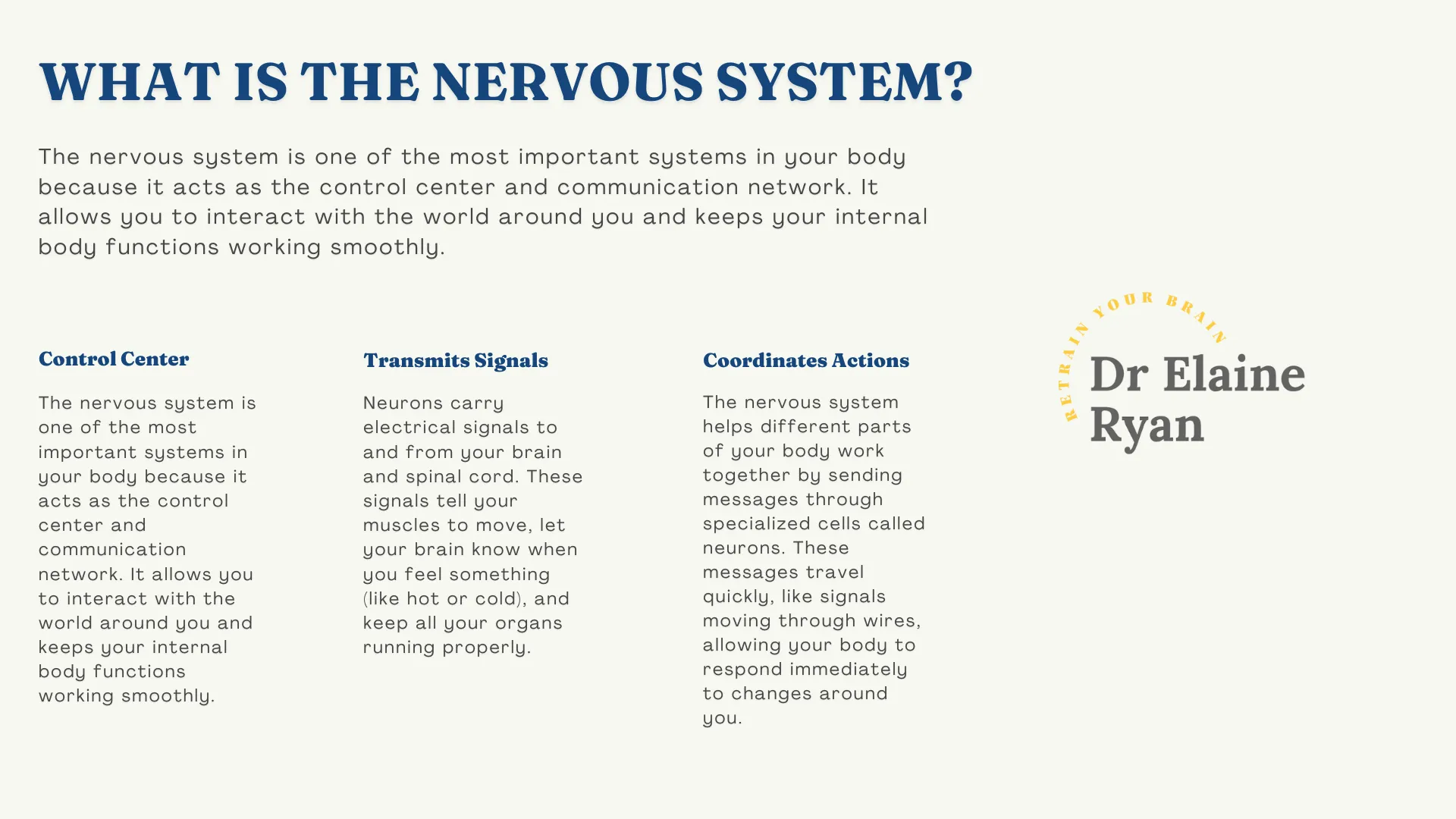

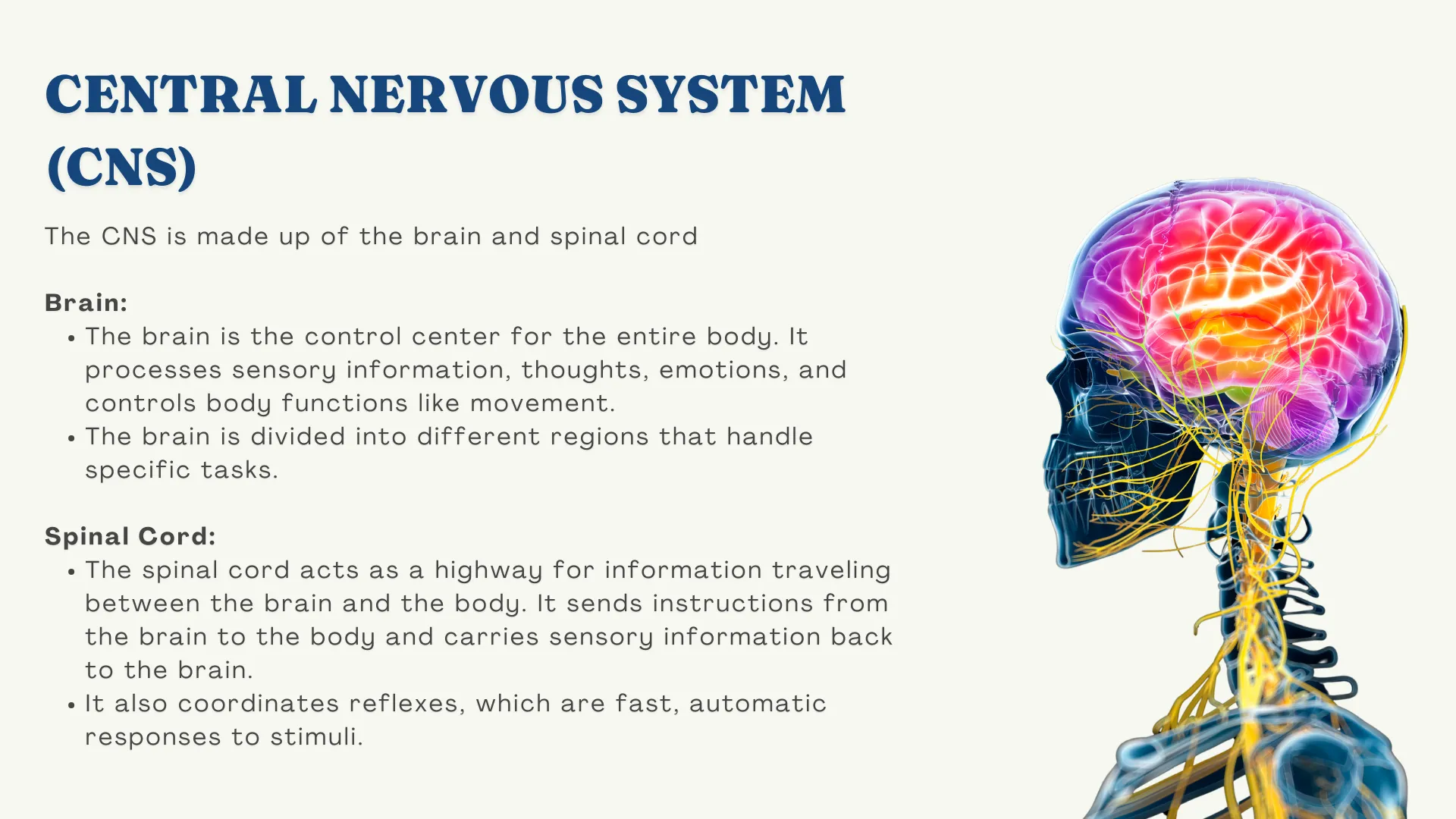

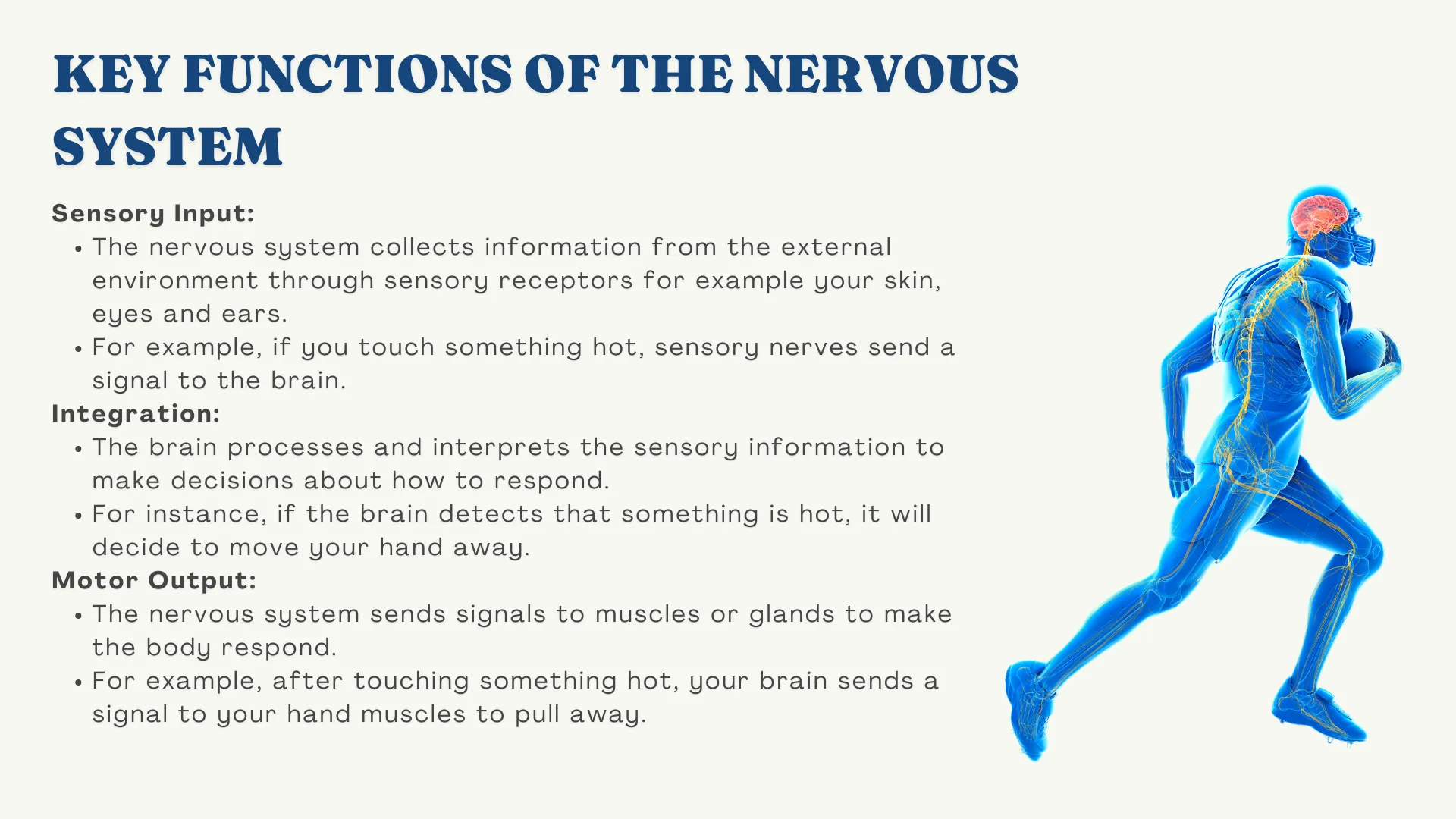

Your Nervous System

The Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) is made up of The sympathetic nervous system SNS, and

The parasympathetic nervous system PNS.

| Symptom | Sympathetic | Parasympathetic |

|---|---|---|

| Heart | Heart beats faster | Heart rate slows down |

| Coronary blood vessels | Dilates | Constrict |

| Lungs | Bronchial muscles relax | Constrict |

| Eyes | Pupils dilate | Pupils constrict |

| Sweat glands | Increased sweating | No effect |

| Salivary Glands | Dry mouth | Watery |

| Bladder | Relaxes bladder | Constrict |

| Digestion | Decreased activity | Increased activity |

| Mental | Increased alertness | None |

| Endocrine Pancreas | Inhibits insulin | Stimulates insulin |

| Kidneys | Decreased urine | Increased urine |

You are normally not aware of the operating of the autonomic nervous system, ANS. It works away, in the background, away from your conscious thought. It works with no effort on your part, like a reflex, adapting and responding to your immediate environment.

It is useful to understand how it works, if you want to understand anxiety and the symptoms that you experience You may be more familiar with the sympathetic nervous system, being called, “fight or flight.” It activates when we perceive we are in some sort of danger.

Example: If, late at night, you see a crowd of young teenagers coming toward you. They are loud and not familiar to you. This scenario might activate the SNS to prepare you to either run away or stand and face whatever happens. You are getting prepared for danger.

Activation of the sympathetic nervous system

- Release of adrenaline and noradrenaline

- Increase heart rate and blood pressure

- Increases blood flow to skeletal muscles

- Inhibits digestive functioning

When the young teenagers come closer and you see they are members of a local community, collecting for “bob – a – job” week, you immediately relax.

You do not consciously decide to relax, you relax as your parasympathetic nervous is activated – rest and digest.

Parasympathetic nervous system activation

- Lowers heart rate, breathing and blood pressure

Let me explain in more detail.

When we are relaxed and ready to kick back and unwind from our day, the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) enables us to do this, by relaxing our body, slowing down the heart rate and blood pressure.

When this happens we can easily relax into our favourite armchair and feel content. This is why some people refer to the PNS as the rest and digest system. Our body slows down and is able to concentrate on digesting our dinner and the removal of waste from the body.

This is not how we want to feel when meeting a bull, as we are not in a state to deal with it.

This is the beauty of the the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) (also know as fight or flight), it takes control of everything you need in the blink of an eye.

One second you are relaxed and content, and the next your heart is pounding out of your chest and you are no longer in that sleepy relaxed state. You are wide awake.

Does this sound familiar? Exactly like panic attack symptoms? Often you can feel ok, and then, out of the blue, your chest hurts, your heart is pounding.

With anxiety, you may have chest pain, difficulty relaxing or sleeping, your mind is racing and you have tummy troubles. With panic attacks, you may struggle to breathe, be sweating, shaking, and think you might die.

Although distressing, it is just your autonomic nervous system thinking that it has detected a threat and activates your SNS to help you out.

Think of your brain as constantly scanning wherever you are for possible danger. Once it detects something, anything, that might cause your harm, it protects you by activating the SNS when you need to be alert and ready to take action.

- Once this happens, your mind is sharper, you become more focused.

- Your bowels and bladder can empty making you lighter and able to run or fight.

- Your senses and vision are no longer sleepy, but sharp and taking in more information.

- Blood gets diverted to your heart to help it pump faster

It then activates the PNS (the rest and digest) when the danger has passed to allow you to relax.

The Autonomic Nervous System: Why Anxiety Feels So Physical

I’ve been a psychologist for over twenty years – and as someone who has personally experienced anxiety, I know how real and frightening the physical symptoms can be. Your heart races, your chest feels tight, your stomach churns, your head spins. It can feel as if your body is betraying you or that something is seriously wrong. But I promise, there is a biological reason for every sensation. It’s not “all in your head” – it’s your autonomic nervous system in action, triggering the well-known fight-or-flight response. In a way, your body is behaving exactly as it’s designed to when it thinks you’re in danger. Understanding this can be incredibly empowering: when you realise why these symptoms happen, they become a little less scary.

Fight-or-Flight: Your Sympathetic Nervous System on “Full Throttle”

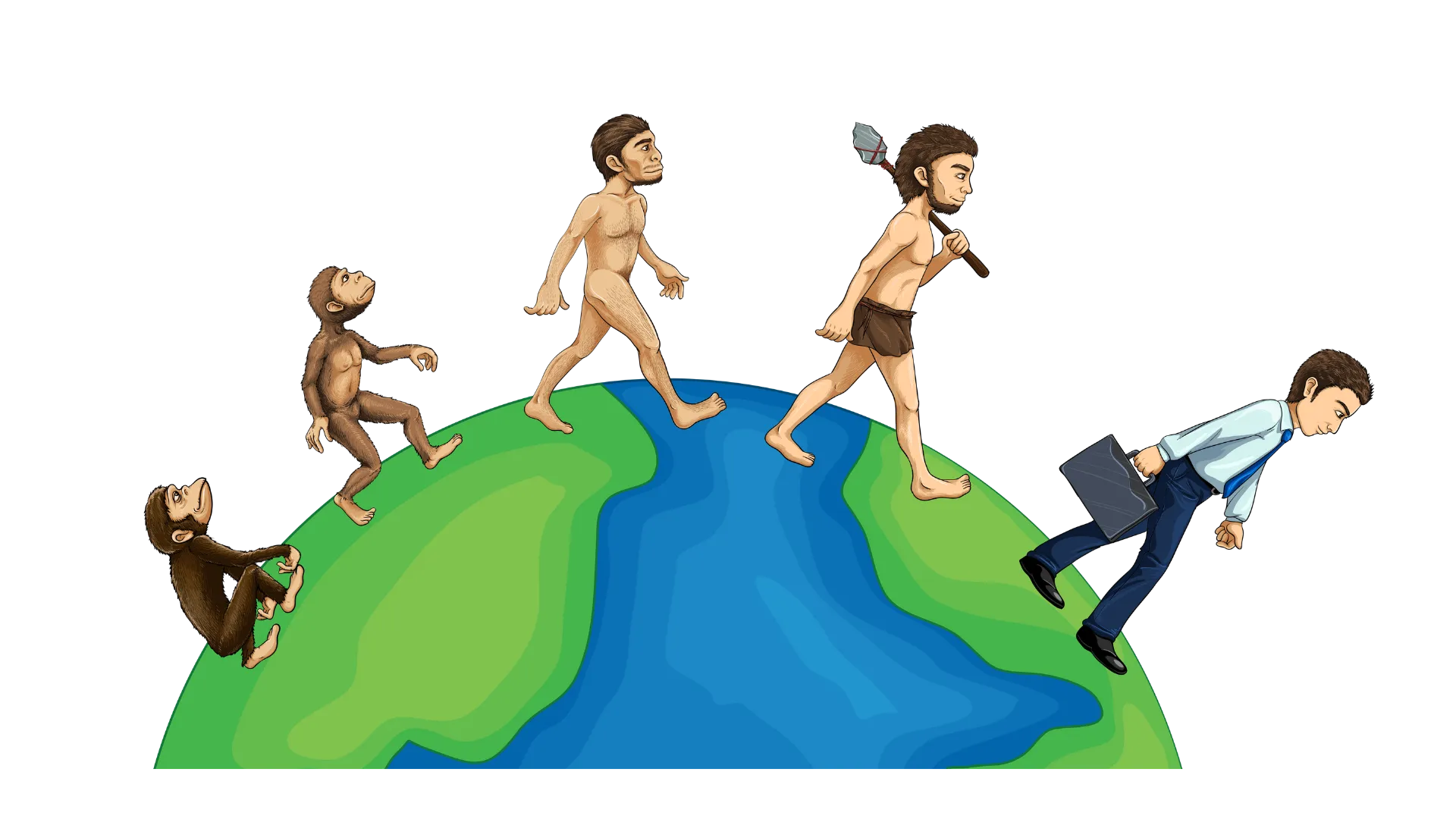

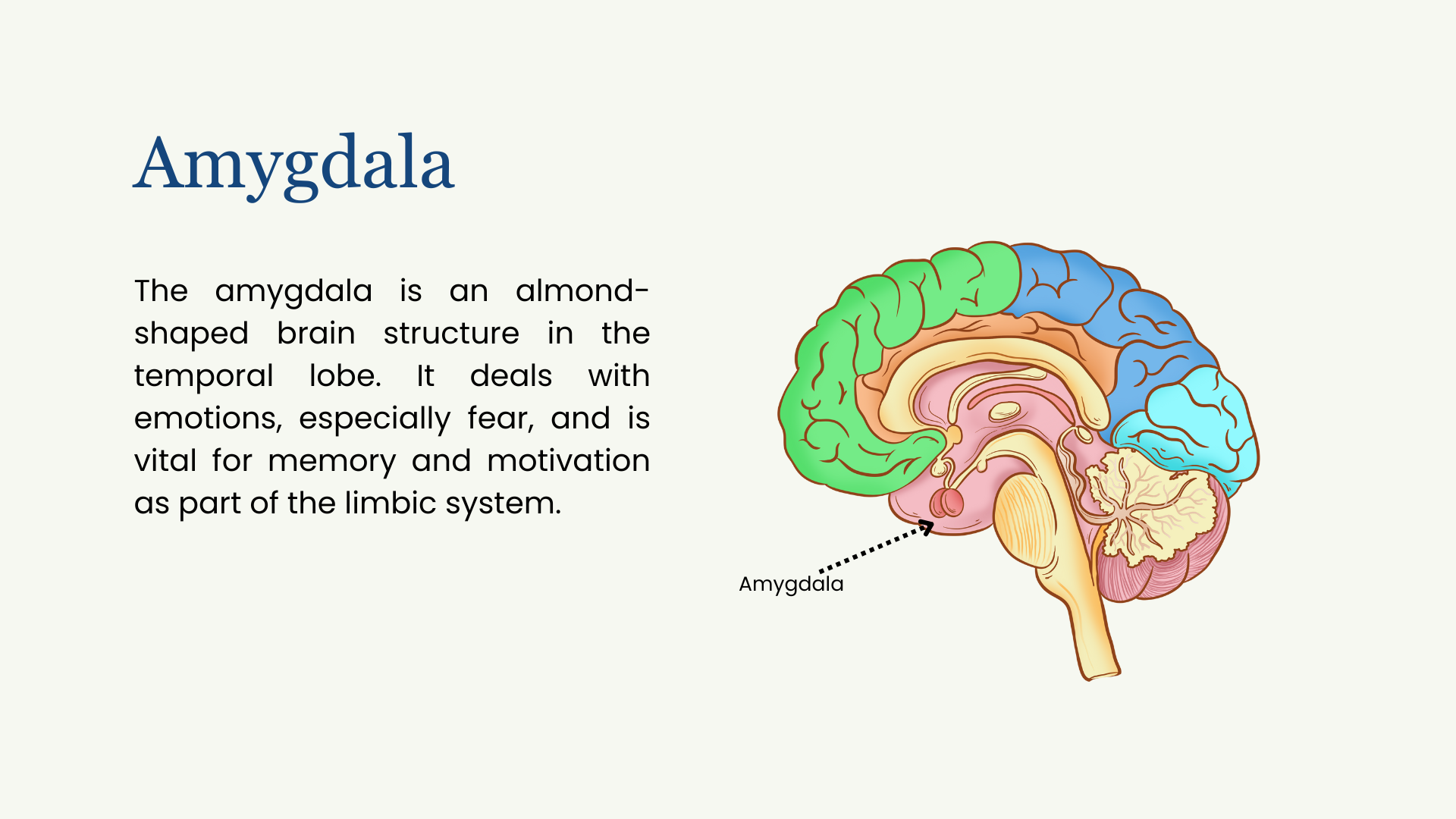

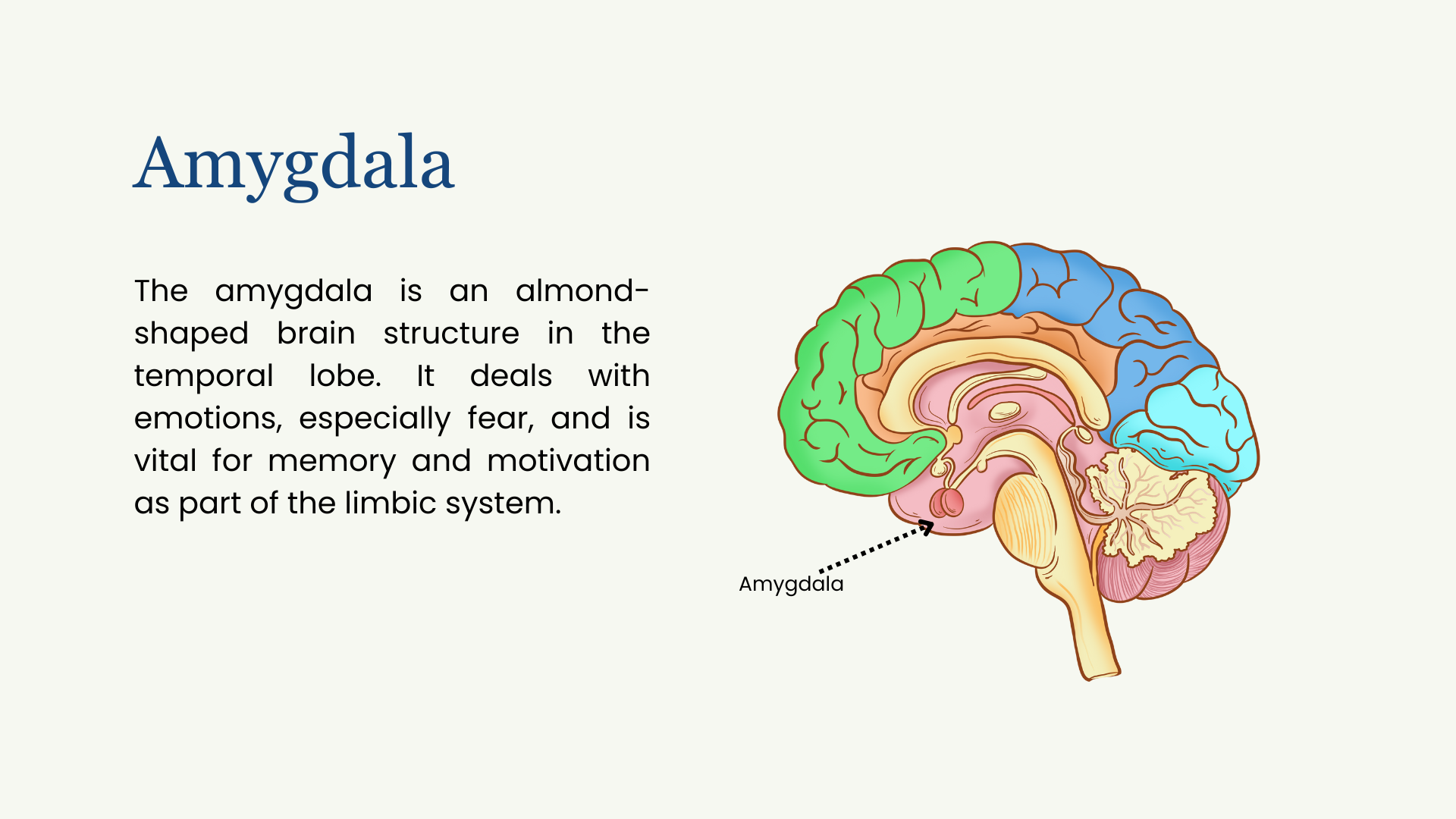

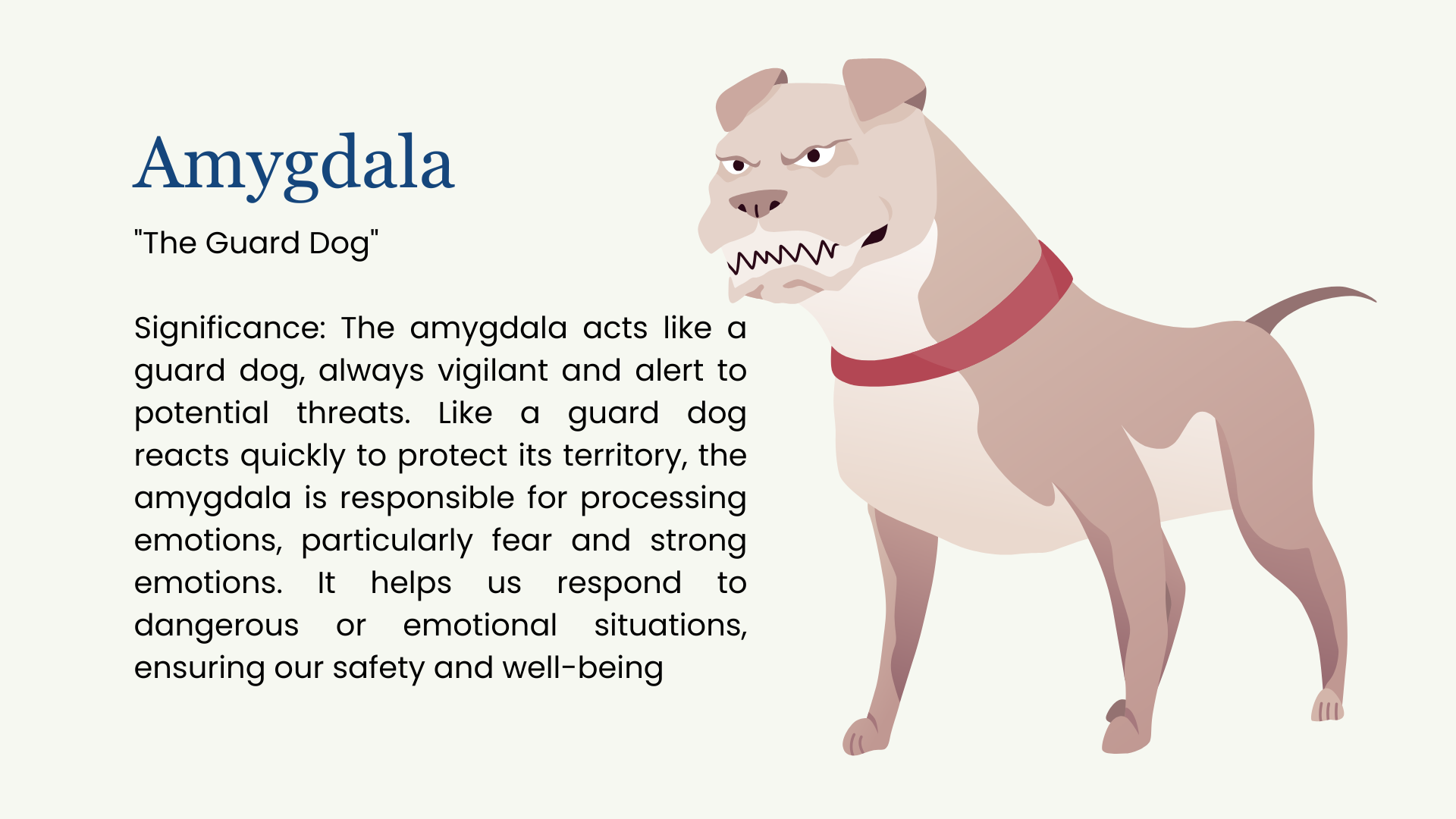

When we perceive a threat (whether it’s a genuinely dangerous situation or just a high-pressure meeting at work), a tiny almond-shaped part of the brain called the amygdala sounds the alarm. Learn more about your amygdala and its role in anxiety.

Harvard Health notes your stress response starts in your brain once information comes via your eyes and alerts the amygdala, that something may be about to happen.

Think of the amygdala as your brain’s smoke detector – it’s always sniffing for danger. Once it detects a possible threat (even a false alarm), it instantly activates your sympathetic nervous system – the branch of your autonomic nervous system responsible for the fight-or-flight response. I often explain to my clients that this sympathetic system is like putting your foot down on the car, all systems go. It sends a lightning-fast signal through your nerves to your adrenal glands (small glands atop your kidneys), telling them to pump out adrenaline (also known as epinephrine) and other stress hormones into your bloodstream and the brake, is like the parasympathetic system -, putting on the brakes to slow everything down again.

Adrenaline is like rocket fuel for your body – it produces a cascade of physical changes that prepare you to either fight for your life or run for the hills. Your heart pounds faster, sending blood rushing to your big muscles and vital organs. Your breathing quickens and your airways expand, pulling in more oxygen. Your blood pressure spikes to circulate that oxygen-rich blood efficiently. Extra oxygen even goes to your brain to make you alert.

Ever notice how you become hypersensitive to your surroundings when anxious? That’s because adrenaline literally sharpens your senses – eyesight and hearing become more acute (I joke that when I’m anxious I can hear a pin drop in the next room – my brain is on high alert, scanning for any sign of danger.) You might start sweating as your body anticipates intense activity and tries to cool you down. Sensory problems can be explained by this activation, as your pupils widen to let in more light, which can make your vision seem brighter or a bit unfocused (some people get blurry vision or “tunnel vision” during high anxiety) Essentially, your sympathetic nervous system has floored the accelerator – giving your body a burst of energy and reflexes to deal with a threat.

This response is amazingly helpful in true emergencies. If you nearly step in front of a bus, that surge of adrenaline and “supercharged” feeling might literally save your life by helping you jump back in time. The problem with anxiety is that the alarm often goes off when there’s no real danger – your body reacts to a stressor or even a worried thoughtas if you’re facing a predator. So you might be lying in bed or sitting in a meeting, and suddenly your heart is thumping and your hands are trembling as though you’re in great peril. It’s disconcerting, to say the least! I’ve had clients tell me, “I felt like I was having a heart attack while watching TV.” I reassure them (and myself when I feel it too) that this is just the sympathetic nervous system doing its job – albeit at the wrong time. Your internal “security system” has essentially triggered a false alarm, but the physical sensations are very real.

Why These Symptoms Happen (From Head to Toe)

Let’s break down some of the most common anxiety symptoms – and a few lesser-known ones – and explain how exactly the fight-or-flight response produces each one. As we go through them, you’ll see that everything you feel during anxiety has a purpose in the context of danger. Your body isn’t malfunctioning; in fact, it’s working beautifully to protect you (though it feels awful in a non-dangerous situation).

Heart Pounding / Palpitations and Chest Pain

One of the hallmark signs of anxiety is a racing, pounding heart. You might feel it hammering in your chest, fluttering, or skipping beats (palpitations). This can be terrifying – I’ve been there, lying in bed convinced I must be having a heart attack. In reality, this rapid heartbeat is your body’s way of delivering oxygen and energy where it’s needed. If you truly were in danger, a fast heart rate would help you run faster or fight harder by pumping blood to your muscles.

The trouble is, when you’re anxious at home, that pounding heart just feels scary. Sometimes the heart beating so hard can cause a sensation of chest tightness or pain. Anxiety-related chest pain is usually caused by a combination of muscle tension and breathing changes. When adrenaline hits, your chest muscles (and those between your ribs) may tense up as your body braces for action, or as Anxiety Canada aptly put it, to allow you to strike out. You might also start breathing very rapidly or hyperventilating without realising it.

Hyperventilation (over-breathing) can cause chest discomfort in two ways: it can lead to muscle spasms in the chest wall and it causes your blood vessels to constrict, which can provoke chest pain. (It’s the same reason some people feel chest pain during a panic attack – it’s not a heart attack, but it feels awful.) The good news is that if your heart is healthy, anxiety chest pain is harmless and temporary. Once your breathing slows and your nervous system calms, that tight chest and thumping heart will pass. I find it helpful to remember that my heart is doing exactly what it’s supposed to in fight-or-flight mode – even if I don’t need all that blood flow right now. Sometimes I’ll even place my hand on my chest and think, “Okay, heart, thank you for trying to protect me. I’m not in danger, you can relax now.” This little acknowledgement can break the fear spiral and start to soothe my nerves.

Shortness of Breath & Dizziness

Along with a pounding heart, many people (myself included) experience shortness of breath or the feeling that they just can’t get enough air. You might take deep gulps, yawn a lot, or feel like you’re suffocating even though you’re actually breathing more than you need. This is usually due to over-breathing (hyperventilation) during high anxiety. Remember, your body is trying to supply extra oxygen for a fight or escape. Paradoxically, breathing too fast can make you feel breathless and light-headed. Here’s why: When you hyperventilate, you blow off too much carbon dioxide, which alters the balance of gases in your blood. Low CO2 causes blood vessels to narrow, according to my.clevelandclinic.org including those that supply the brain.

Less blood flow to your brain is what makes you feel dizzy, lightheaded, or faint – it’s like the woozy feeling after spinning around. I’ve had moments of acute panic where I suddenly go light-headed and my vision starts to dim at the edges; it’s scary, but it’s essentially because I was unconsciously over-breathing. The key thing to remember is that this dizziness and air hunger are not actually dangerous – you are not going to stop breathing or pass out (in fact, fainting from anxiety is uncommon because blood pressure is usually high, not low). Your body is actually getting plenty of oxygen; it’s just that the balance is off.

One trick I use is to slow down my breathing (for example, exhale slowly as if blowing out a candle, or breathe into cupped hands) to raise carbon dioxide back to normal – this often eases the dizzy, breathless feeling within a minute or two. Again, the symptom has a purpose: if you were about to sprint or fight, breathing fast is adaptive. But when you’re just sitting and worrying, it just makes you feel weird. Recognising that “Okay, I’m feeling dizzy because I’m anxious and my CO2 is low” can help you stay calm and ride it out until your body steadies.

Muscle Tension, Aches, and Trembling

Ever notice how tense your muscles get when you’re anxious? It’s as if your body is bracing for impact – which is exactly what it’s trying to do. Adrenaline prepares your muscles to spring into action. They tighten up to make you a smaller target and to ready themselves to either fight (think of a boxer tensing their muscles) or to run (a sprinter’s muscles primed to explode off the blocks).

This muscle tension can occur anywhere: you might clench your jaw (I personally get a stiff neck and jaw on stressful days), hunch your shoulders, or ball up your fists without noticing. Over time, this leads to soreness – I often hear people with anxiety complain of back pain, stiff neck, or headaches from chronically tight muscles. Sometimes the muscles shake or tremble, especially in the arms or legs. I’ve had clients describe their knees wobbling when they were anxious in a crowd, or their hands shaking during a panic attack. That trembling is a side effect of your muscles being flooded with adrenaline and energy. Think of a racing dog quivering at the starting line – so much energy is coursing through its muscles that it literally shakes. In anxiety, your body is ready to move now, but if you’re standing still, that energy has nowhere to go, resulting in visible shakes or internal jittery feelings. Again, it’s helpful to remember that this is normal: your body is behaving like a warrior gearing for battle. Once you start to calm down (or if you engage those muscles in actual movement, like taking a brisk walk), the trembling subsides as the excess adrenaline burns off. A useful tip: try progressive muscle relaxation or simply stretching/rolling your shoulders when you notice tension – this sends a signal to your brain that it’s okay to hit the brakes. Which brings us to…

“Rest-and-Digest”: The Parasympathetic System and Digestion

This is where you take your foot off the accelerator and hit the brakes. As I noted in the video at the start of this article, this occurs outside of your conscious awareness and is controlled automatically, but, fortunately for those of us with stress or anxiety, you can learn how to hit the brake yourself, and teach your body to calm down, but first I am going to explain what this ‘rest-and-digest’ system is.

When your brain’s alarm is turned off, the parasympathetic system directs blood back to your internal organs, and digestion resumes its normal pace. But during anxiety, the brake is essentially off and the accelerator is floored, meaning digestion is not a priority. If you’ve ever had butterflies in your stomach before a big event, or an upset tummy when stressed, that’s fight-or-flight at work. The sympathetic response actually slows down your digestive process. Food might just sit there because, from your body’s perspective, why bother digesting lunch when you’re in danger? Better to save that energy for escaping. As a result, people with anxiety often experience nausea, indigestion, or stomach cramps. In my case, my appetite vanishes when I’m extremely anxious – my body effectively says “we’ll deal with food later.” On the flip side, some folks get increased acid production and heartburn (or reflux) because the stomach isn’t emptying normally. If the anxiety is severe enough (like a panic attack), you might even feel like you could vomit. It’s all part of the body’s way of clearing the decks for action.

Bowel and bladder

Along with stomach upset, bowel habits can change with anxiety. It’s not the most glamorous symptom, but it’s very common: stress can speed up bowel motility in some people, leading to urgent trips to the loo or even diarrhea. (There’s a reason for the old phrase “I was so scared I nearly s*** myself” – pardon the language – or having “the runs” from nerves.) On the other hand, ongoing anxiety can also contribute to constipation for some, since digestion is slowed; everyone’s gut response is a bit different.

And what about that classic nervous pee? Many of us find we have to urinate much more frequently when anxious. You might go to the toilet twice before an exam, or feel like a tiny bladder on a first date. This is an evolutionary quirk: in a real life-or-death scenario, emptying your bladder and bowels lightens your load so you can run faster. It’s truly a built-in survival mechanism – albeit an inconvenient one in modern life! The take-home point is that your churning stomach, knots in your gut, or sudden need to visit the bathroom are not random – they are direct results of your nervous system’s activation. As uncomfortable (and sometimes embarrassing) as these symptoms are, they make sense in light of the body’s strategy to protect you. When the danger (or rather, the false alarm) passes and your parasympathetic “brakes” kick back in, your digestion will normalize again – the butterflies calm down, nausea fades, and appetite returns.

Strange Sensations: Tingling, Numbness, Hot Flushes

Anxiety can produce some truly odd sensations. One common but often alarming symptom is a feeling of tingling or numbness, especially in the hands, feet, or face. The first time I experienced a full-blown panic attack, I remember my fingers went tingly and my face around my mouth felt almost numb – which, of course, made me panic even more. But here’s what’s happening: during fight-or-flight, blood is redirected away from your extremities (hands, feet, even skin) and sent to the big muscles and vital organs. This shunting of blood can cause a transient pins-and-needles feeling or numbness in the less critical areas.

Additionally, if you’re breathing rapidly, the changes in blood chemistry can contribute to that prickly sensation (people who over-breathe often get tingling in their fingers or lips). It’s actually the same mechanism as when your hand “falls asleep” from reduced circulation – anxiety is temporarily altering your circulation. Rest assured, it’s harmless and will reverse once you calm down and your blood flow normalises (in fact, tingling is often one of the first signs that you’re hyperventilating, and doing some slow breathing can help resolve it).

Anxiety can also play tricks with your body temperature. You might get sudden hot flushes (blushing bright red or feeling a rush of warmth to your face and neck) or, conversely, feel chilled to the bone with cold, clammy hands. The warmth and flushing come from adrenaline’s effect on blood vessels – in some cases, it causes them to dilate (open up) in your skin, leading to that wave of heat or redness (think of how some people’s faces turn red when they’re anxious or embarrassed – that’s adrenaline at work. On the other hand, blood being pulled to the core can leave your extremities cool, making you shiver or get goosebumps. I’ve had clients with social anxiety describe feeling their face burning with heat (blushing) during a stressful interaction, which only made them more self-conscious. It helps to know that this is a natural physiological response – your body is redirecting blood flow and pumping out heat as it revs up. Practically, if you’re dealing with this, using a cool cloth on your face or removing a sweater can provide relief for the hot flushes, and doing some jumping jacks can warm you up if anxiety gives you a chill. The main thing is: these sensations might feel bizarre, but they’re not dangerous. They are signs that your nervous system is in high gear.

Sight and hearing

Anxiety doesn’t only make you feel things more intensely in your body – it can also make the outside world seem louder, brighter, and harsher. This is another byproduct of adrenaline’s job of heightening your senses for survival. Vision changes are common: you might become sensitive to light, notice your surroundings look overly sharp or “too real,” or conversely experience a bit of blurriness. As mentioned, your pupils dilate during fight-or-flight to improve your vision in the dark or to spot movement easily. In a modern setting, that can mean indoor lights suddenly feel glaring or you see floaters or shadows that weren’t there before. Some people even get tunnel vision (where peripheral vision narrows) during panic – it’s the body’s way of focusing on the threat straight ahead. I’ve had times when anxiety made everything seem like it was in ultra-high definition, almost overwhelming my sight.

Similarly, hearing becomes more acute – your ears strain to pick up every sound of “potential danger.” This can make you jump when the phone rings or feel on edge about noises that normally wouldn’t bother you. On the flip side, some anxious folks report feeling distant or unreal, as if sounds are muted – this can be due to the mind dissociating a bit under stress, a way to tune out overwhelming input. But typically, it’s hyper-sensitivity. You’re essentially in hunter mode, like a deer perked up at every twig snap. While this sensory overload is uncomfortable (crowded places or bright stores might overstimulate you during high anxiety), remind yourself: my body is trying to protect me by boosting my senses. Once you relax, your pupils will constrict and your hearing will settle back to normal. Some find it helpful to wear sunglasses or noise-cancelling headphones in the throes of anxiety – a little trick to reduce input and signal to your frazzled brain that it’s okay to dial things down.

Insomnia and Restlessness

One symptom that often gets overlooked in the moment (but we sure notice it at night) is difficulty sleeping when our anxiety has been high. After an anxious day, you might lie in bed utterly exhausted yet completely unable to fall asleep – your body and mind refuse to shut off. This is the classic fight-or-flight aftermath: your system is still flooded with adrenaline and cortisol (a longer-acting stress hormone), keeping you on alert. Stress hormones elevate your heart rate and body temperature, and stimulate your brain, making it hard to drift into sleep. In fact, the SleepFoundation notes studies have shown that stress and anxiety often lead to insomnia and other sleep problems. It becomes a vicious cycle because lack of sleep then makes you more anxious the next day, and so on.

I’ve had many nights where I’m tossing and turning because my body feels wired – my muscles are tense, I’m rehashing worries, and every time I start to drift, I get that jolt awake (sometimes called a “hypnic jerk,” which can be more frequent when you’re overstressed). This is essentially your nervous system having trouble shifting from the sympathetic (alert) state into the parasympathetic (relaxed) state. When we finally do fall asleep under high anxiety, the sleep might be light and filled with weird dreams, because our brain is still a bit on guard. If this happens to you, know that it’s very common. I often advise clients (and do myself) to practice a wind-down routine: dim lights, deep breathing exercises, maybe a calming herbal tea – basically, anything that tells your body “the danger has passed, you can power down now.” Over time, as you teach your body that it’s safe at night, your sleep can improve. And if you have an occasional rough night, remind yourself that even resting with eyes closed is helpful and that your body will eventually rebalance (I sometimes literally say to myself in the dark, “It’s okay, body, there’s no emergency now.” It sounds corny, but speaking to your anxious brain in a gentle, reassuring way can activate that calming parasympathetic response).

Feeling Empowered: Your Body’s Intention is Protection

That was a lot of information, but I hope walking through it this way helps you see a clear pattern: anxiety symptoms are the direct result of your body’s hardwired survival system. Every racing heartbeat, every bead of sweat, every jittery or queasy feeling – it’s all rooted in the fight-or-flight response that’s been with us since humans lived in caves. The range of symptoms is so wide because the autonomic nervous system touches nearly every part of the body (from your eyes to your gut to your skin). On the bright side, this means that these symptoms, as varied and upsetting as they are, are predictable and explainable by science. In my experience, both personally and professionally, understanding this brings a huge sense of relief. I vividly remember the first time I learned about the sympathetic nervous system in grad school – a lightbulb went off. So I’m not crazy, and I’m not dying – it’s just adrenaline and my anxious brain! This realization took away some of anxiety’s intimidating power over me.

Knowledge is power. When you notice your anxiety flaring up and your body revving into overdrive, try to remember: This is my autonomic nervous system trying to help me. It may be a false alarm, but my body doesn’t know that. Instead of feeling victim to your symptoms, you can almost take a curious observer stance: “Ah, my heart is racing and I have that lump in my throat – my fight-or-flight must have kicked in. Thanks, amygdala, but there’s no real danger right now.” It might sound funny to talk to your amygdala, but by responding to your symptoms with understanding (rather than panic), you’re engaging your thinking brain and telling the fear center that it can stand down. This compassionate self-talk can actually reduce the intensity of the symptoms. Remember, we also have that wonderful parasympathetic “brake” system. We can encourage it to activate through slow breathing, relaxation techniques, or even simple reassurances of safety. I often guide people through breathing exercises to stimulate the vagus nerve (a key nerve in the parasympathetic system) which helps calm the heart rate and relax the body. It’s pretty amazing – just as your body has a built-in way to rev you up, it also has built-in ways to slow you down. It might take some practice to fully tap into those, especially if your “alarm” has been oversensitive for a while, but it is possible.

Above all, I want you to take away that you are not alone in feeling these bizarre anxiety symptoms, and there’s nothing “weak” or “broken” about you for having them. I’ve worked with countless clients in Ireland and around the world who describe the exact sensations you do. And as someone who still wrestles with anxiety on occasion, I truly feel what you’re going through. These symptoms can be tough, but they are temporary and they will pass as your nervous system settles. By learning about the autonomic nervous system’s role, you’re equipping yourself with insight that can help you cope. Next time your heart is thudding or your vision goes funny from panic, you might remember this explanation and think, “Okay, this is uncomfortable but it’s my body’s natural response – I can ride this out.” In that moment, you move from fear to understanding, and from understanding to a bit more control. After all, what is anxiety itself but the feeling of not being in control? Explaining the science is one way to hand some control back to you. And from my 20+ years of experience, when you feel understood – even by yourself – and understand what’s happening in your body, the anxiety loses some of its grip. You’ve got this, and your body is on your side (even if it doesn’t feel like it at times).

In summary, the autonomic nervous system (through its sympathetic branch) orchestrates the wide range of anxiety symptoms we experience – from chest pain and dizziness to stomach upset and sleepless nights. It does so in an attempt to protect us, preparing our minds and bodies to face threats that often aren’t truly there. By recognising this and engaging the calming parasympathetic response, we can find ways to navigate anxiety with greater ease and self-compassion. Your body is not your enemy; it’s a guardian that sometimes sounds a false alarm. And with understanding, practice, and support, you can teach that guardian to be a little less jumpy, allowing you to reclaim calm and carry on with confidence.

Now that you understand what is behind all the symptoms you experience, I want to focus on, when and how you get anxious, as this information helps inform your treatment options.

Where do you feel anxious?

Different parts of your brain, result in different experiences of anxiety.

Anxious for no reason

In the same situations

In thoughts and worries

You were not born anxious

You had to learn to be anxious

Your brain is captain of your ship. And more than likely, you have never read the instruction manual. This instruction manual is very important, otherwise your brain may be steering you places that you don’t want to go. To continue the metaphor, if you feel you are out at sea with your anxiety, and that you have no control, it is crucial that you understand your brain, as it is here, that you gain understanding, and eventually, control.

Dr Elaine Ryan

Your 3 brains

It is important to understand all three as they may be working together to give you anxiety.

Note: Paul MacLean introduced the idea of The Triune Brain, and I refer to it here as it is easier to understand that the biological names; you’ve probably come across other clinicians or writers talking about lizard brain, rather than calling it the limbic system.

Your Reptilian Brain

This was the first part of your brain to evolve.

It manages things that you don’t have to think about, unconscious processes such as breathing, temperature and the fight or flight response (for those of you that have panic attacks, you have probably already read about the stress response.)

This is your survival instinct. It always watches out for you, but can over react to day to day things. Your reptilian brain was the first part of your brain to evolve. It is very basic, it doesn’t think, and acts on an instinctual basis.

Can it kill me or will I kill it?

Although it can get you into trouble in terms of anxiety, it is a very useful instinct to have. If you are in danger, your brain reacts instantly, rather than relying on the slower, more intelligent part of your brain, where you would have to stop and think what to do. There is not time to weigh up all your options and decide the appropriate course of action if you have just stepped out in front of a bus.

This part of your brain is always on guard for you, even though you are not aware of it. Everywhere you go, it keeps an eye on potential danger. It regulates things that you do not have to even think about, like your heart rate, and the fight or flight response. It can however, protect you a little too much, as it really can’t tell the difference between a real danger or you just mulling over a real danger in your head.

In order to recover from anxiety, that occurs for no reason, you have to learn to calm down your instinctual reactions.

What does it feel like?

Or another example would be the intense physical feelings you get when watching a scary movie.

You react to the movie as if it where real.

This primitive part of your brain really can’t tell the difference.

Your reactions to the scary movie in terms of physical sensations, are down to the primitive part of your brain.

If you avoid scary movies in the future or think about the movie later, in the cold light of day, and still feel some fear, this is to do with other parts of your brain taking over and I shall talk about this now in terms of your mammalian brain.

Important Points to note

Your reptilian brain reacts to dangers, that are not really there. Your imagined dangers, your worries.

Your reptilian brain reacts without thinking, but then doesn’t do much else. On it’s own, its okay.

But when this interacts with your mammalian brain, this 2nd part of the brain can start to attach emotions. It remembers your fear.

Your mammalian brain

Like the reptilian brain, these emotional responses occur without any effort on your part, outside of your control.

They occur automatically.

This can help to explain why you feel anxious for no reason, giving for example a presentation, driving your car, or just out with friends. It has a lot to do with how your brain attaches emotion to certain memories

Your mammalian brain is better know as The Limbic system or your feeling brain

Your mammalian brain includes the amygdala, which is fundamental to understanding and treating anxiety.

The amygdala is left out of many treatment models.

If you have tried things in the past to help with anxiety and think that ‘it failed,’ take heart, you maybe didn’t have the right tools.

You will have read previously (or if not, go back and read it now ) that your reptilian brain protects you from the basis of it’s survival instinct.

Your mammalian brain can do quite a bit more, in that it has emotions. Not only that, it can attach feelings to what has happened.

For example, say you had a bad time with your boss and had difficulty getting through a presentation at work.

Your mammalian brain can attach the feeling (maybe embarrassment, stress, anger or panic ) to the event; your boss and the presentation.

It can do more than that, it can form emotional memories. Now when you recall your boss or the presentation and are telling people about your bad experience, you can feel it too.

If that occurs again and again, your brain is very quick to learn, and the next time you give a presentation in front of your boss, images and feelings, drawn from your emotional memory, are there for you. You panic!

You will know that your reptilian brain produces the fight or flight response. ‘Will it kill me, or do I kill it?’

This is such a primitive part of your brain, but gets activated now that your brain has matched ‘boss’ ‘presentation’ and ‘fear’ together, but it is really not helpful to have such a strong reaction each time you have to do a presentation in front of your boss.

Neuroscience points the way, letting you know that you can ‘unmatch’ this, or learn a different way for your brain to behave.If this is currently happening to you, it is just your brain.

Your mammalian brain is non verbal, it speaks to you by releasing chemicals.In order to fully recover from anxiety, you need to know what your brain does with this. How it learns, and that is more to do with your rational, intelligent brain.

Your thinking brain

Unfortunately, it is also responsible for a large amount of unnecessary suffering, depending on how you use your brain.

If you think a lot, plan for the worst case scenario; you might get stuck in certain thought patterns. Maybe you keep going over situations that have occurred in the past, or that might occur in the future, you need to look here.

If you have tried to get over anxiety or panic before and didn’t succeed, it might have been that you just tackled one of the above areas.You need to Retrain Your Brain to encourage a different style of learning, and to decrease the things that are keeping you anxious.

This is the brain that most of you will associate as being your own mind or your brain.

Your thinking brain is conscious.That said, you would think that it is under your control, but for many of you, it can feel that it has a mind of its own.

I am going back to the example I used when I was telling you about your mammalian brain – where you got anxious during a presentation with your boss. (, if you haven’t already done so.)

If you immediately forgot about the presentation, everything is well and good in your world. But this is not the normal response for your thinking brain.

Your thinking brain is intelligent, much more so than your reptilian (which is instinctual, gets you ready to fight your boss), and your mammalian (which stores your bad feelings with the memory of your boss and the presentation.)

Your thinking brain searches for meaning. It will desperately try to make sense of what happened at the presentation and fuel your thought processes to look for answers.

Was I nervous before I went in? What happened? It will also allow you to tell your friends about it, and/or and go over and over it again in your mind and feel the anxiety all over again.

Your 3 brains in action

Your thinking brain, rather than being in control, can feel like it is at the mercy of your reptilian and mammalian brain, as it cannot rationalise what has happened.

Reptilian Brain: gave you your fight or flight response

Mammalian Brain: allowed you to attach the fear and anxiety to the memory

Thinking Brain: now worries about it happening again, and you actually start to create, not only a learning curve, but anticipatory anxiety.

You are not aware of it, but you are forming a habit in your brain as your brain assembles all of this information together.

You are, in fact, forming a neural pathway (a network) in your brain connecting all of these things together. Unfortunately, it is an anxiety based learning that is forming in your brain.

Retrain Your Brain

There are a few less understood things that are important to understand if you want to get rid of anxiety.

How your brain learns and,

the function of automatic processes

What are you teaching your brain?

Your anxious brain

Your stress and relaxation response

Reversing your anxiety in your brain

Retrain Your Brain®

Find the root cause of your anxiety.

Retrain Your Brain®

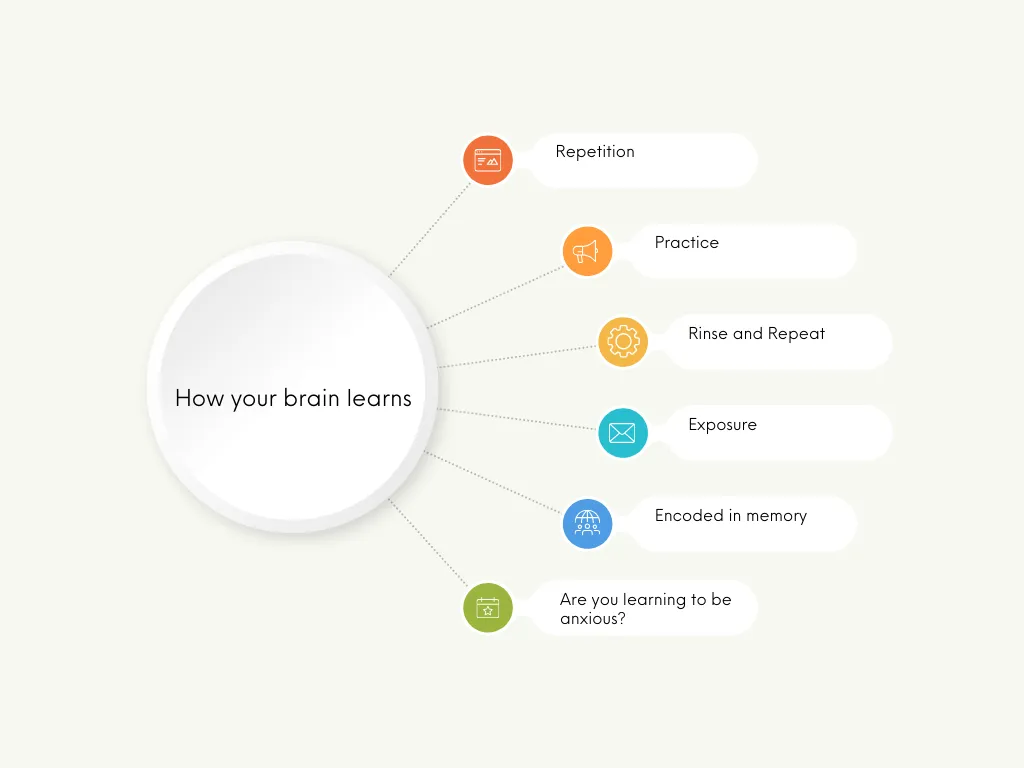

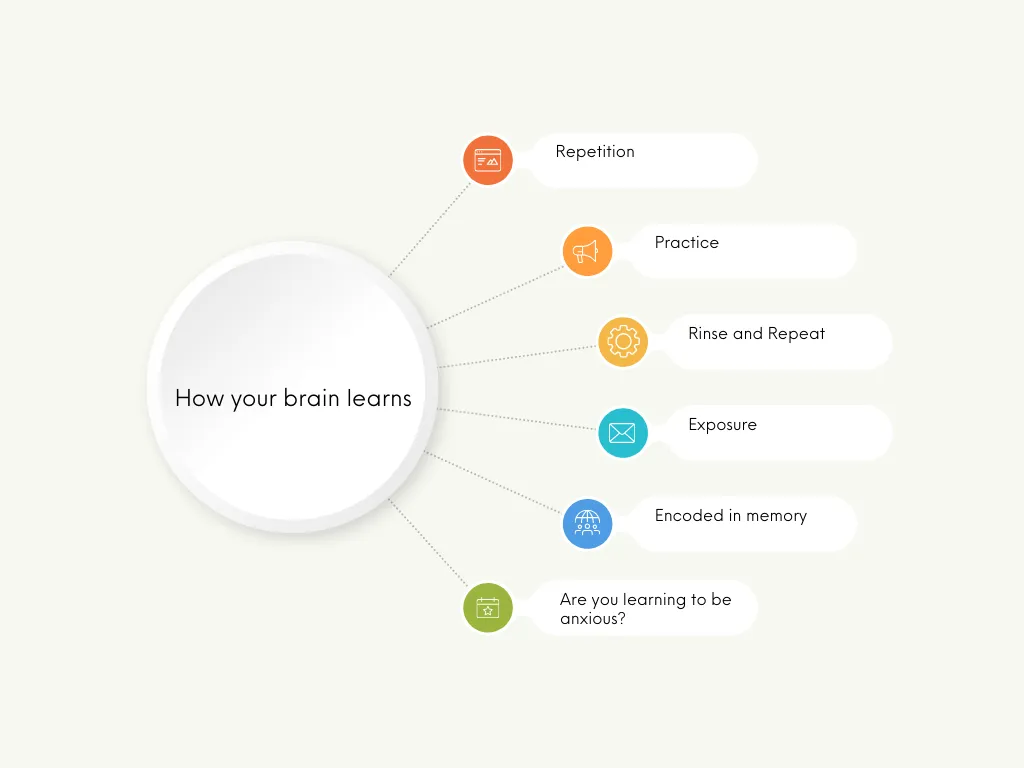

How your brain learns

Your brain

You can only do one thing at a time. If you don’t believe me, try this:

Count from one to ten in your head while you are reading what I am writing. You struggle.

You will struggle more if I tell you to stop reading, count to ten in your head, and recite the alphabet backwards at the same time.

Could you do it? No.

Your brain cannot actively process and give your full attention to more than one thing at a time.

You will of course, be able to do more than one thing at a time, we all multi-task. To be able to do this, your brain has to learn how to make most of the things that you do, automatic.

This is where you can run into trouble, as you may well have automatic processes that not only explain your anxiety, but also keep you anxious.

Due to the nature of these automatic processes, you will be repeating them all the time.

Your brain and automatic processes

When you paid attention to spelling and reading in school, with practice, it became real – you are reading this page.

Not only can you read it without trying, you can also understand it.

You may not know what is happening in your brain to allow you to read and understand, you just know you understand. It became automatic.

It became real.

When you pay attention to something, your brain learns by creating neural pathways or connections. You can think of these pathways as building blocks. The building blocks for reading this page started when you were 4 or 5 years old.

Practicing reading built up and strengthened the building blocks until now you can read this page with no difficulty. Everything to do with reading, spelling and understanding is stored in your brain

The more you practiced, the stronger the association became, until your practice paid off; reading became automatic. Practice makes perfect.

It is the same with anxiety; everything to do with anxiety will have its own neural pathways (building blocks) in your brain.

It is not the anxiety that is the problem, but how you habitually think, and how you habitually react, that creates problems in your life.

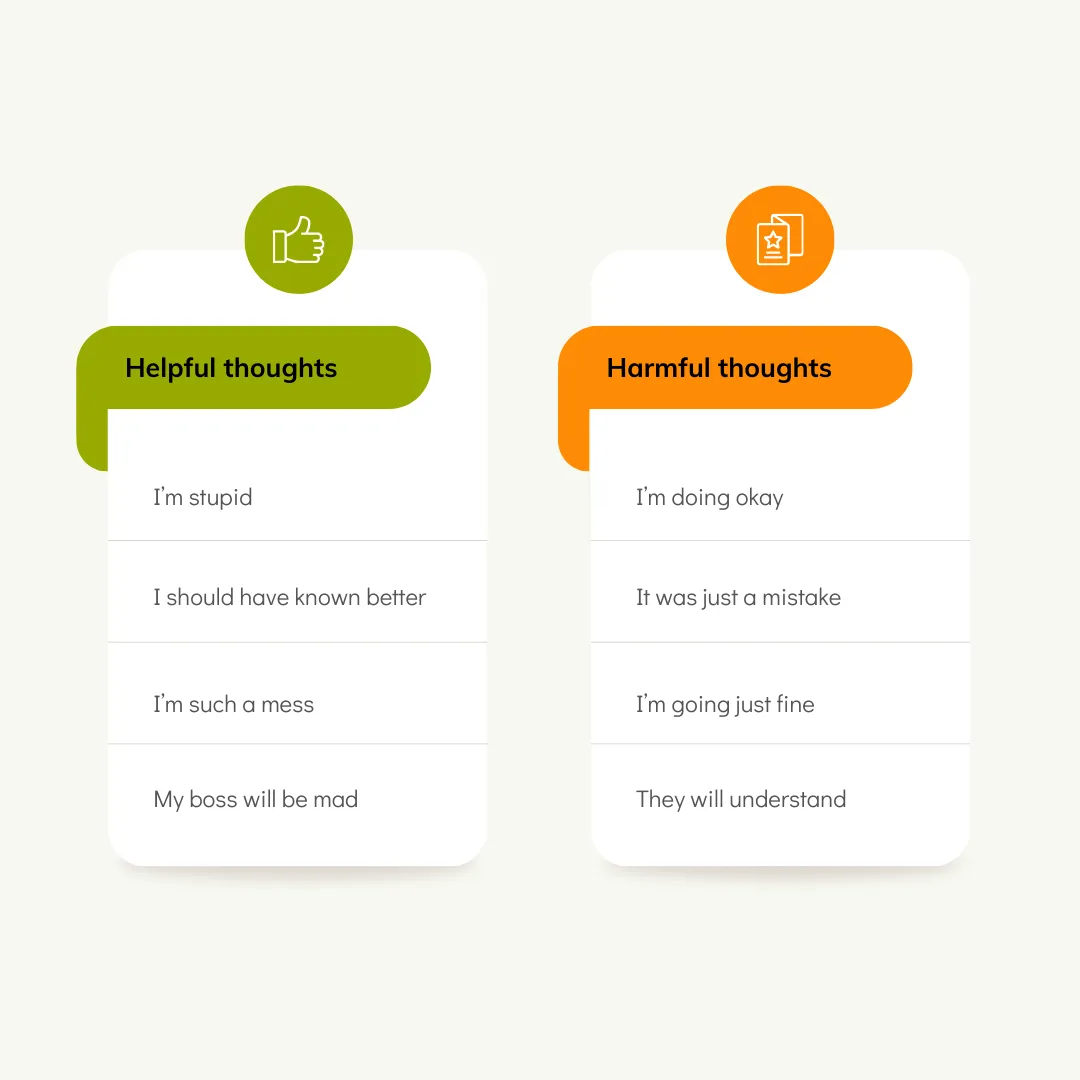

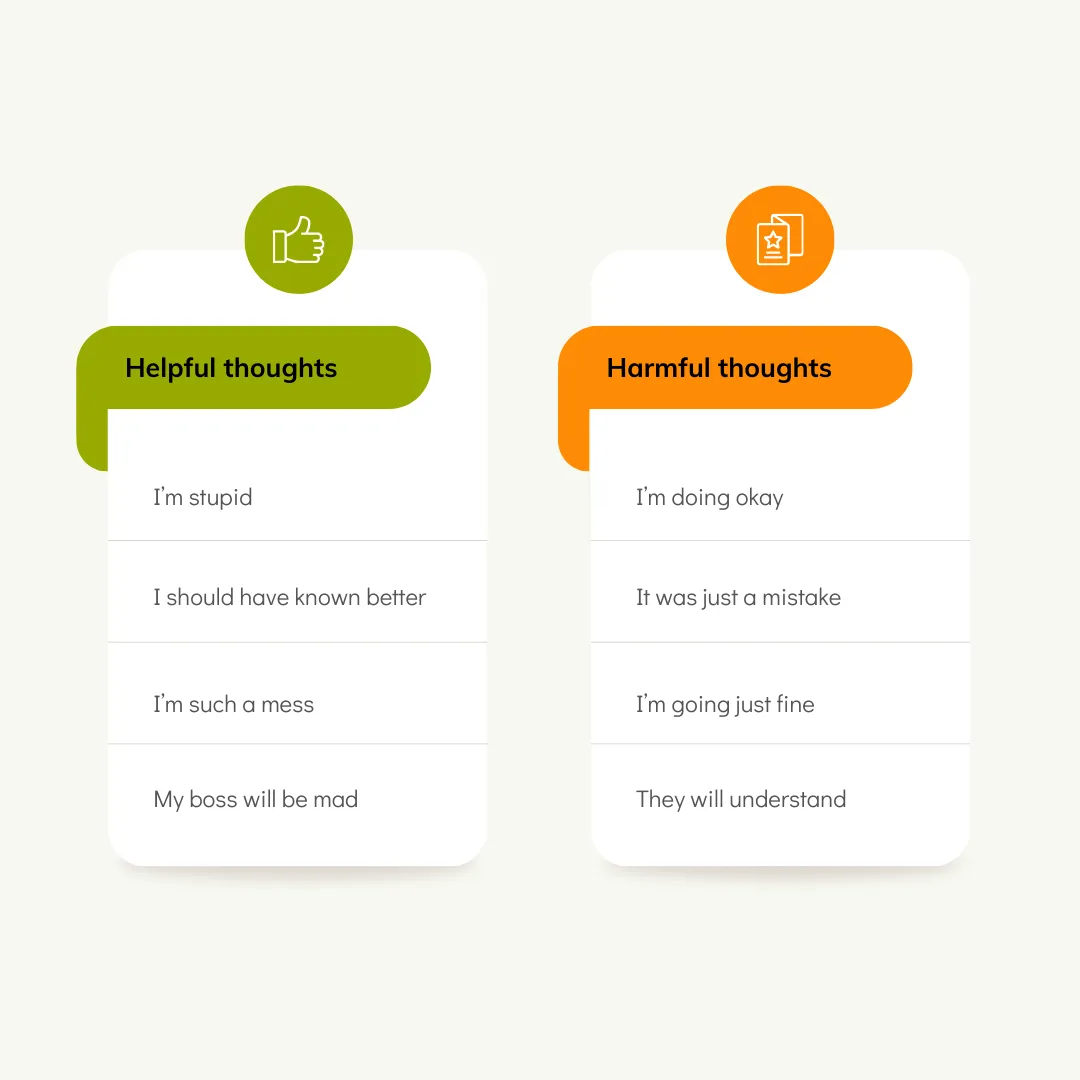

What are you teaching your brain?

Are your thoughts helpful to you or are your thoughts harmful to you?

If you discover you are your own cheerleader, you can stop reading.

If you are like the rest of us (myself included), you may well have found that your thoughts do not help you out all the time

For example: You are late for work and it will take you one hour to get there. If you accept this situation and are nice and calm, you might enjoy the hours journey. More than likely you might be upset, annoyed, or giving out to yourself inside your head, “I should have got up earlier, “I should have taken another route”, and you may feel anxious when stuck in traffic.

These thoughts are related to how you respond to what is actually happening: you are late for work. Being late for work in itself, cannot cause anxiety. How you respond; can.

Unfortunately they may be part of a well-trodden path in your brain, sort of like a script, or a switch that turns on, giving you:

- Negative self talk;

- Feelings of anxiety or anger;

- Worry about what will happen.

If this is how you usually react, this well-trodden path in your brain gives you stress, automatically.

These ‘pathways or connections’ that become automatic, can be very powerful: you can slip back into the anxiety habit and not know why.

It’s why organizations, schools and the emergency services run drills, over and over again. In a crisis, they don’t think. They do what they have been trained to do, what has been drilled to become automatic. They have a well-trodden automatic path that allows them to respond without thinking.

Your anxiety has become a well-trodden path, always available to you in certain (or maybe all) situations.

Your habitual thoughts and reactions may have taught your brain to be anxious. Once taught, these habitual thoughts and reactions make sure that you stay anxious.

You were not born anxious.

Your brain is primed to pay more attention to negative experiences rather than positive ones, as the negative ones may harm you.

As I said before, it is not the anxiety that is the problem but how you think about it and how you respond to it.

If in the above example, you worry about being late, and feel stressed, anxious or angry at being stuck in traffic, your brain is alert to this negative situation.

The dangers that your brain is responding to, are no longer life-or-death situations, but day-to- day experiences.

Deadlines;

Money worries;

Work/school;

Relationships.

All the ‘self-talk’ that goes on inside your head.

Your anxious brain is always on the look out for possible ‘danger.’ When there is no real danger there, your mind takes over, and worries, races; you expect the worse.

Physical symptoms, maybe even panic attacks develop. The pathway in your brain for anxiety becomes stronger. It is able to connect your worries with the physical symptoms in your body.

If you worry about a meeting, or dread going somewhere in case you have anxiety, your brain pays attention to this. New pathways are created relating to anxiety. Now if someone mentions the ‘meeting’ or the place ‘you dread going’ your anxiety pathway is activated, and your brain can give you everything related to anxiety.

Your worries, the physical symptoms, they all appear automatically. Just like reading this page.

You can now feel anxiety in many situations and not know why.

You have your own automatic pilot for anxiety.

What your brain pays attention to becomes real.

You are now living with an automatic stress response

What is a stress response and a relaxation response, and why they are important?

The following is a copy of a webinar, even though the webinar was on panic attacks, and I would recommend watching it to answer some questions about the stress response.

The course I refer to in the video

The stress response and nervous system is covered in detail about, but I shall give another example as a refresher. Let’s take an example of sitting in your favourite armchair after dinner.

If your brain and body is working well for you, it will do the following:

Your rest and digest nervous system will give you a relaxation response, to relax your body and help you to digest your food. You feel comfortable and relaxed. The relaxation response is what helps you to kick back and unwind from your day.

Suddenly there is an extremely loud bang in the other room.

Your brain takes over and gives you a stress response to make you feel alert and able to move quickly to see what has happened.

One second you are almost asleep and the next your heart is pounding and you are in the other room. Does that sound familiar? One second you feel ok and the next you feel stress or anxiety?

You see that your dog knocked over a stool and you calmly walk back to your favorite armchair.

Soon your heart rate has slowed down and you are feeling comfortable again, as your nervous system has replaced the stress response with a relaxation response (rest and digest.) You fall asleep.

This is how our nervous system should work for us, giving us stress when we need it, and relaxation at other times. However, if you experience any form of stress, you will be feeling the effects of the stress response in many situations where you do not need to.

You may find it difficult to kick back and relax, and feel the benefits of the relaxation response as you are on constant high alert – getting the stress response too often when it is not needed.

Your brain is primed for stress and associates the small things in life with stress. Each time you encounter them, your brain gives you stress.

I would like to reassure you that science shows that you can change the way your brain is working for you. Your brain changes during your life depending on the thoughts that you have and how you react to all the different experiences that you encounter in your life.

In order to reverse your anxiety, you need to Retrain Your Brain®

I do not want to fill your head with miracle cures; rather I want to offer a no nonsense, practical explanation to why you feel stressed, burned out, and anxious.

I want to show you how to pay attention differently. To give you control over what is happening. To help you to create new building blocks in your brain. Ones that are more helpful to you. If you want to step out of automatic pilot mode, say goodbye to your unwelcome anxiety and take control of what is happening, then I invite you to have a look at my Retrain Your Brain Program.

Recap. So far we have discussed anxiety, understood the symptoms and different ways it can occur. Now, I want to talk about the different types. If you end up meeting someone like myself, a psychologist, we would conduct an assessment, not just to tell you whether or not you have anxiety, but also to tell you what type you have, and I shall outline the main anxiety disorders below.

Types of Anxiety Disorders

Generalised Anxiety Disorder GAD

Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD) is a common mental health condition characterised by persistent and excessive worry about a wide range of everyday things. You can learn more about the symptoms, causes, and treatments for GAD on my dedicated Generalised Anxiety Disorder page.

- Worries out of proportion to the situation

- It’s very difficult to control your worry even though you know it is not helping

- Worry affects many aspects of your life, such as how you cope in work, your relationships and your health.

- You probably have physical symptoms, feeling restless but also tired, hence the expressions ‘tired but wired.’

Panic Disorder

Panic disorder is more than having a panic attack, with panic disorder you have repeated attacks over an extended period of time and that interfere with your life.

During a panic attack, you might experience:

- Racing heart

- Chest pain

- Shortness of breath

- Feeling like you can’t catch your breath

- Choking or smothering sensation

- Dizziness

- Lightheaded

- Shaky

- Sweating or chills

- Feeling sick, tummy upset

- Scared that you are going to lose control and ‘go crazy.’

Example. You’re driving to work, something you have done many times before, when suddenly, your heart starts pounding, you feel dizzy, and your chest tightens. This is terrifying, especially when you are in control of a car, or on the M25 going into London! You might feel like you’re having a heart attack or that you’re about to lose control. This is what a panic attack can feel like. Learn about the differences between anxiety and panic attacks.

People with panic disorder often worry about having more panic attacks and may start to avoid situations where they fear an attack might happen. In the example I used above, it is understandable if the person tries to avoid driving.

Learn more about Panic Disorder, its causes, and effective treatments on my Panic Disorder page

Phobias

A phobia is much more than not liking something. For example, I am much better now with spiders, I am not overly keen on them, but don’t fly into a tailspin if I see one. In my professional life, I have worked with a client who moved house as they could not find a spider. That is a, albeit, an insane, phobia. A phobia is an intense, irrational fear of a specific object or situation. People with phobias often go to great lengths to avoid their triggers, as with my client, which can significantly disrupt their lives.

Common types of phobias:

Specific Phobia

where you are afraid of a specific object or situations, for example, blood, animals, flying.

Agoraphobia

Fear of situations where escape might be difficult or help unavailable, such as using public transportation, being in open spaces, being in enclosed spaces, standing in line, or being in a crowd. This often occurs with panic disorder.

Social Anxiety Disorder

Social anxiety, also known as social phobia, is more than just being shy. It’s an intense fear of social situations where you might be judged or negatively evaluated. This can lead to avoiding social gatherings, public speaking, or even everyday interactions like making phone calls or eating in public. Learning how to overcome social anxiety can greatly improve your quality of life.

Example: Imagine you’re at a party. You feel like all eyes are on you, judging your every move. Your heart races, your palms sweat, and you just want to disappear. This is a glimpse into what it’s like to live with social anxiety. It can make it incredibly difficult to connect with others and enjoy social events.

Learn more about Social Anxiety Disorder

Separation Anxiety Disorder

While often associated with children, separation anxiety can also affect adults. It involves excessive fear or anxiety about being separated from people you’re attached to. This can lead to constant worry, clinginess, and difficulty being alone or away from loved ones.

Example: An adult with separation anxiety might experience intense anxiety when their partner goes on a business trip. They might have persistent worries about something terrible happening, struggle with sleep, and find it challenging to function until their loved one returns.

Selective Mutism

Often first noticed in childhood, selective mutism involves a consistent inability to speak in specific social situations, despite being able to speak in other settings. This can significantly impact a child’s school performance, social development, and overall well-being.

Example: A child with selective mutism might speak freely at home with their family but remain completely silent at school, even when asked direct questions by teachers or classmates.

The HSE provides information on selective mutism and how to get a diagnosis.

Less Common Anxiety Disorders

In addition to the common types discussed above, there are other anxiety disorders that you might encounter:

- Substance/Medication-Induced Anxiety Disorder: Anxiety caused by the use of substances (e.g., alcohol, drugs) or withdrawal from them.

- Anxiety Disorder Due to Another Medical Condition: Anxiety directly caused by a medical condition, such as hyperthyroidism, heart problems, or neurological conditions.

- Other Specified Anxiety Disorder and Unspecified Anxiety Disorder: These are categories used when someone experiences significant anxiety that causes distress or impairment but doesn’t fully meet the criteria for any of the specific anxiety disorders.

Each anxiety disorder has distinct triggers and patterns, but all can be addressed by understanding their underlying thought–feeling–behaviour cycles.

Cause of Anxiety: Understand the Factors

Anxiety typically arises from a mix of factors:

Thought Patterns

Negative thinking, catastrophising, mind-reading.Learned worry behaviours from caregivers or past experiences. Constantly dwelling on worst-case scenarios, overestimating threats, or engaging in self-criticism can trigger and fuel anxiety. Learn more about anxiety triggers.

Cognitive Distortions: These are inaccurate or unhelpful thinking patterns that make us more vulnerable to anxiety.

Brain Chemistry & Genetics

Imbalances in neurotransmitters (serotonin, GABA, norepinephrine).

Amygdala: This small, almond-shaped structure acts as the brain’s alarm system, processing emotions, particularly fear and anxiety. When it perceives a threat (real or imagined), it triggers the stress response, preparing the body to fight or flee. Learn about the role of the amygdala in anxiety.

Prefrontal Cortex: This area is responsible for decision-making, planning, and impulse control. It helps regulate the amygdala’s response and assess whether a perceived threat is real or not.

Neurotransmitters: These are chemical messengers that transmit signals between brain cells. Imbalances in neurotransmitters like serotonin, GABA, norepinephrine, and dopamine can contribute to anxiety.

Family history of anxiety can increase your vulnerability.

Life Experiences

Traumas, chronic stress, sudden life changes.

Modern stressors (e.g., workload, finances, social media pressures).

Environmental & Lifestyle Factors

Poor sleep, high caffeine or alcohol intake, inadequate stress management.

How to Know if You Need Professional Help

A stepped-care approach is often used:

- Mild Anxiety: Try self-help (books, online resources) and lifestyle changes first.

- Persistent or Worsening Anxiety: Consider therapy (e.g., CBT) and/or medication.

- Severe Anxiety: May require specialized or intensive treatment, combining multiple modalities and professional oversight.

If you follow a stepped-care approach, you may not need treatment by a psychologist, as you can start with self-help. I would have used a stepped care approach when working in the UK, and see that the HSE adopts the same. The idea of this type of working is to do with resources, efficiency and cost, for example, it does not make sense to use all the resources of a mental health team to help someone with mild anxiety, self- help may suffice. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE for short) gives guidance on a Stepped Care Approach, which suggests

- Assessment, education and discussion of treatment options

- This could be a meeting with your local GP, who diagnoses anxiety or refers you to a psychologist for psychological assessment. Your GP or mental health consultation will explain anxiety to you and recommend treatment options, which may start with self-help.

- Self-Help

- This can be self-help that you undertake alone on in groups

- CBT with a Psychologist

- If self-help does not work for you, you might be referred to someone like myself, a psychologist for CBT.

- Highly Specialised Treatment

- When I worked in the UK I was part of a highly specialised multi-disciplinary team where people would be seen by psychologist, have psychiatrists to monitor medication and could also involve in-patient care.

If anxiety interferes with your work, relationships, or overall well-being despite self-help efforts, seek professional guidance.

Diagnosis

If you suspect you might have an anxiety disorder, it is essential to meet with a licensed mental health professional; a psychologist or psychiatrist can undertake an assessment and tell you not only if you have anxiety, but what type you have.

The clinician will use a tool called the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). According to the DSM, the criteria for anxiety include the following;

- excessive anxiety and worry most days about many things for at least six months

- difficulty controlling your worry

- the appearance of three of the following six symptoms: restlessness, fatigue, irritability, muscle tension, sleep disturbance, and difficulty concentrating

- symptoms significantly interfering with your life

- symptoms not being caused by the direct psychological effects of medications or medical conditions

- symptoms aren’t due to another mental disorder (e.g. anxiety about oncoming panic attacks with panic disorder, anxiety due to a social condition, etc.)

Anxiety Treatment Options with Dr Elaine Ryan Dublin

Whether you decide to make an appointment to see me for psychological therapy in my clinic in Dublin or meet with another therapist, this final section of the article will give you a good overview of what you need to do and who you should see if you decide to seek professional help with your anxiety.

Anxiety counselling – talk therapy rooted in science

Your GP may have referred you for anxiety counselling with someone like myself, a psychologist, and in this section I want to explain how therapy will help you.

It’s “Talk Therapy,” But It’s Also Science

When people hear “talk therapy,” they often picture a patient lying on a couch, free-associating for years while the therapist interprets unconscious conflicts (think classic psychoanalysis). But that’s not the approach we’re discussing here.

In modern, empirically supported therapies, like Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), we do talk—absolutely—but every conversation is guided by scientific principles that have been rigorously tested in studies worldwide. We look at the connections between your thoughts, feelings, and behaviours, then use research-backed techniques (e.g., thought-challenging, behavioural experiments) to help you change unhelpful patterns and reduce anxiety. Learn more about how CBT can help with anxiety.

- Structured & Goal-Oriented: Instead of wandering through endless childhood memories, we pinpoint specific issues in your present life and work methodically to address them.

- Data-Driven: We might keep track of your mood, do short exercises during or between sessions, and evaluate what’s working—just like in a scientific experiment.

- Time-Efficient: CBT (and similar approaches) are often designed to be short- to medium-term, focusing on practical skills you can master relatively quickly.

Yes, there’s talk—but it’s a purposeful, guided conversation that blends empathy with a science-based framework, ensuring you’re not just venting your feelings but learning tools proven to help you move past anxiety.

The Science of CBT for Anxiety: How It Works

At My Therapist, my approach to anxiety treatment is grounded in science. I use evidence-based therapies like Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), which have been rigorously tested and proven effective in numerous studies and recommended by organisations like NICE (UK) and the HSE (Ireland).

What is CBT?

Instead of treating anxiety like a mystery, models such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy CBT map your thoughts, emotions, body sensations, and behaviours—so you see exactly where things go off-track. For example, at the start of this article I asked you to record some data and now we can use that data to demonstrate some of the practical aspects of CBT. We shall do a ‘chain analysis’ in a moment to show you how some of the principles of CBT work.

CBT for Anxiety – How it Works

Picture anxiety as four interlinked parts:

- Trigger/Situation

- Example: An email about having to present at work.

- Thoughts

- “I’ll embarrass myself in front of everyone.”

- Feelings/Emotions

- Fear, dread, worry.

- Physical Sensations

- Racing heart, sweaty palms, tense shoulders.

- Behaviour

- Avoid the meeting, over-prepare obsessively, or skip it altogether.

These pieces reinforce each other: the alarming thought increases your physical symptoms, which heightens fear, which leads to avoidance—and that can confirm your fear was justified. Recognizing this cycle is the first step to breaking it.

Chain Analysis: Understand why you got anxious using CBT

Forward Chain (Trigger ? Thought ? Feeling ? Behavior)

- Identify the initial situation (seeing the email), the worry (“I’ll fail”), the emotional spike (fear), and how you act (avoid).

Backward Chain (Behaviour ? Feelings ? Thought ? Trigger)

- Start with your final action (cancelled the meeting) and step backward to see the emotions, the underlying thought, and the original trigger.

Why It Helps:

- You see exactly where you could pause, challenge a thought, or use a coping strategy to prevent the full-blown spiral.

Grounding, thought-challenging, and exposure exercises aren’t just ideas; they’re backed by controlled studies showing they reduce anxiety and help people cope better in daily life.

Because CBT follow a tested blueprint, when you apply them step by step, you’re using the same approach that’s helped countless others recover from anxiety.

CBT and Scientific Models Give You a Roadmap for Change

Step-by-Step Progress: Scientific models don’t rely on guesswork. They lay out a method: identify the anxious thought, challenge it, observe the change in your feelings, and practice new behaviours. Each time you use these techniques, you reinforce healthier patterns in your mind and body. This isn’t pseudoscience; it’s a well-documented process called “neuroplasticity.”

In Practice: Another Quick Example of How to Apply CBT

Situation: You get invited to speak at a work event.

- Old Pattern:

- Thought: “I’ll definitely make a fool of myself.”

- Feeling: Fear/dread.

- Body: Racing heart, tense stomach (overactive amygdala).

- Behaviour: You find a reason to cancel or avoid.

- Using the Model:

- Identify & Challenge: “Is it certain I’ll fail? I’ve spoken up in meetings before without catastrophe.”

- Physiological Shift: Practice slow breathing for 1 minute, calming the fight-or-flight surge.

- New Behaviour: You decide to at least attend and share one brief comment.

- Scientific Backing: Studies show repeating this pattern weakens fear pathways and strengthens confidence pathways in the brain (neuroplasticity).

As you keep applying these tested methods, you’re essentially telling your brain: “This isn’t a real threat—calm down.” Over time, your anxiety response decreases. Science-driven approaches don’t just mask symptoms; they aim to rewire the thought-feeling-behaviour loop.

Bottom Line

Using scientific models means relying on strategies proven to help people better understand and manage anxiety. You’re not just following a “hunch” or a “guru’s” advice; you’re applying decades of psychological and neuroscientific research in a structured, step-by-step way—and watching how your mind and body begin to change for the better.

Medication

In some cases, medication can be helpful in managing anxiety symptoms, especially when combined with therapy.

Antidepressants: Certain antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors(SNRIs), are commonly used to treat anxiety disorders. They work by affecting the balance of neurochemicals in the brain.

Anti-anxiety Medications: Benzodiazepines can provide short-term relief from anxiety symptoms, but they are generally not recommended for long-term use due to the risk of dependence and side effects.

Working with a Psychiatrist: It’s important to consult with a psychiatrist for medication management. They can assess your needs, prescribe appropriate medication, and monitor its effects.

Self Help

My Self-Help Course: My online course, “Retrain Your Brain,” provides a comprehensive program for overcoming anxiety. You’ll learn practical strategies to reduce worry, manage physical symptoms, and improve your overall well-being.

Self-Help Strategies for Managing Anxiety

Relaxation techniques: Deep breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation, and meditation can help calm your body and mind.

Mindfulness exercises: Paying attention to the present moment without judgment can reduce worry and rumination.

Exercise and physical activity: Regular exercise has been shown to reduce anxiety symptoms and improve mood.

Healthy sleep habits: Getting enough sleep is crucial for managing anxiety. Establish a regular sleep schedule and practice good sleep hygiene.

Stress management techniques: Learning to manage stress effectively can help prevent anxiety from escalating.

Online Resources: There are various online anxiety resources that you can access.

For additional community-based support and resources, consider contacting Aware.ie or exploring resources tailored for younger individuals on SpunOut.ie.”

How to deal with anxiety right now

If you are feeling anxious right in this very moment, the remainder of this article includes videos I made to help you with guided relaxation. They are only short-term strategies and do not replace meeting with a mental health professional for assessment and treatment.

If you are feeling anxious right now, the following brief videos will help you manage your current anxiety.

Controlled breathing

The following video will help you to control your breathing.

7-11 breathing

“Dr. Elaine Ryan is a Dublin-based psychologist with a proven track record in treating anxiety disorders. With over 20 years of experience, she offers compassionate and effective therapy to help individuals overcome their challenges. To schedule an appointment or learn more about Dr. Ryan’s services, please feel free to contact the clinic.”

References

Ekman P. Basic Emotions. Handbook of Cognition and Emotion. 2005:45-60. doi:10.1002/0470013494.ch3

Hockenbury, D. and Hockenbury, S.E. (2007). Discovering Psychology.New York: Worth Publishers.

Vora, E. (2022) The anatomy of anxiety. Orion Spring