Anxiety is one of the most common mental health difficulties – and also one of the most treatable. But feeling anxious doesn’t always mean you have an anxiety disorder, and not everyone with anxiety will need formal treatment. If you do need therapy, I provide evidence-based anxiety treatment in Dublin and online across Ireland, including CBT and exposure based approaches.

I’m Dr Elaine Ryan, a psychologist in Dublin. Anxiety is one of the main things I work with, and I’ve also had anxiety myself, panic disorder to be specific. My job is to spot the specific patterns maintaining your anxiety, explain them in clear, plain English, and guide you step-by-step as you learn practical skills that reduce anxiety for the long term.

If you are ready to start, the following options are open to you.

- arrange an appointment (therapy), or

- start my structured self-help course for anxiety; Retrain Your Brain®, available immediately

Or if you are not sure, please keep reading as my page will explain what works for anxiety, as well as giving detailed guidance on what anxiety is.

Book an Appointment / How to Get Started

You don’t need a GP referral to contact me. If anxiety is interfering with your sleep, work, relationships, or daily life — therapy can help.

In your first appointment we’ll map out what’s happening for you, what type of anxiety you’re dealing with, and what approach is most likely to work.

Psychological therapy for anxiety

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is one of the most recommended treatments for anxiety in Ireland or indeed anywhere as it is an effective gold standard treatment for anxiety disorders. Gold standard means it is evidence based, where it has been extensively researched and shown to be effective for anxiety, with high success rates.

Exposure Therapy should also be used, often as part of CBT, as anxiety is maintained by avoidance. Exposure therapy is used to help you stop avoiding things in a controlled and safe way.

Table of contents

- Psychological therapy for anxiety

- Medication

- What is Anxiety?

- Evolution of Anxiety

- Where do you feel anxious?

- Your 3 brains

- Retrain Your Brain

- Find the root cause of your anxiety.

- Different Pathways to Anxiety

- In order to reverse your anxiety, you need to Retrain Your Brain®

- Types of Anxiety Disorders

- Cause of Anxiety: Understand the Factors

- How to Know if You Need Professional Help

How I See Anxiety (and Why That Matters for Treatment)

A lot of people talk about anxiety as if it’s a mysterious force that descends on you from nowhere.

Clinically – and from my own lived experience – I see it differently.

Anxiety is an emotion with three main components:

- What you feel in your body – racing heart, tight chest, dizziness, nausea, tension.

- What you think – “What if…?”, catastrophising, self?criticism, worries about the future.

- What you do (or avoid) – cancelling plans, “just in case” behaviours, checking, googling symptoms.

Those components connect into patterns. And patterns can be understood, predicted and changed.

As a psychologist, I don’t think of myself as an anxiety “guru” with secret tricks. I’m someone who is:

- well trained in evidence based therapies (especially CBT and exposure?based approaches), which are recommended as first line treatments for anxiety disorders in national guidelines

- experienced – I’ve sat with people who have had almost every form of anxiety you can imagine

- informed by my own history of anxiety and panic, which keeps me grounded in how it actually feels

Those therapy models give us maps that show how anxiety works in the mind and body. My job in treatment is to:

- spot the specific patterns that are maintaining your anxiety

- explain them in clear, plain English

- teach you practical ways to change those patterns so anxiety no longer dominates your life

You don’t need to become an expert in psychology. You need someone who can break it down and guide you through the steps. That’s what this treatment page – and my work with clients – is about.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is the main psychological treatment for anxiety disorders worldwide. Large reviews of studies consistently show CBT is effective for conditions like panic disorder, generalised anxiety, social anxiety and health anxiety.

At its heart, CBT focuses on the connection between:

- Thoughts – what you tell yourself about situations (“I can’t cope”, “I’ll have a heart attack in this queue”).

- Feelings – anxiety in the body and emotions (fear, dread, shame).

- Behaviours – what you do in response (avoid, escape, seek reassurance, check).

Over time, certain thought?behaviour loops keep anxiety going, even when you desperately want it to stop.

In CBT for anxiety, we work together to:

- Identify unhelpful thinking patterns – like catastrophising, over-estimating threat, mind?reading others’ opinions, or assuming you “couldn’t cope” if X happened.

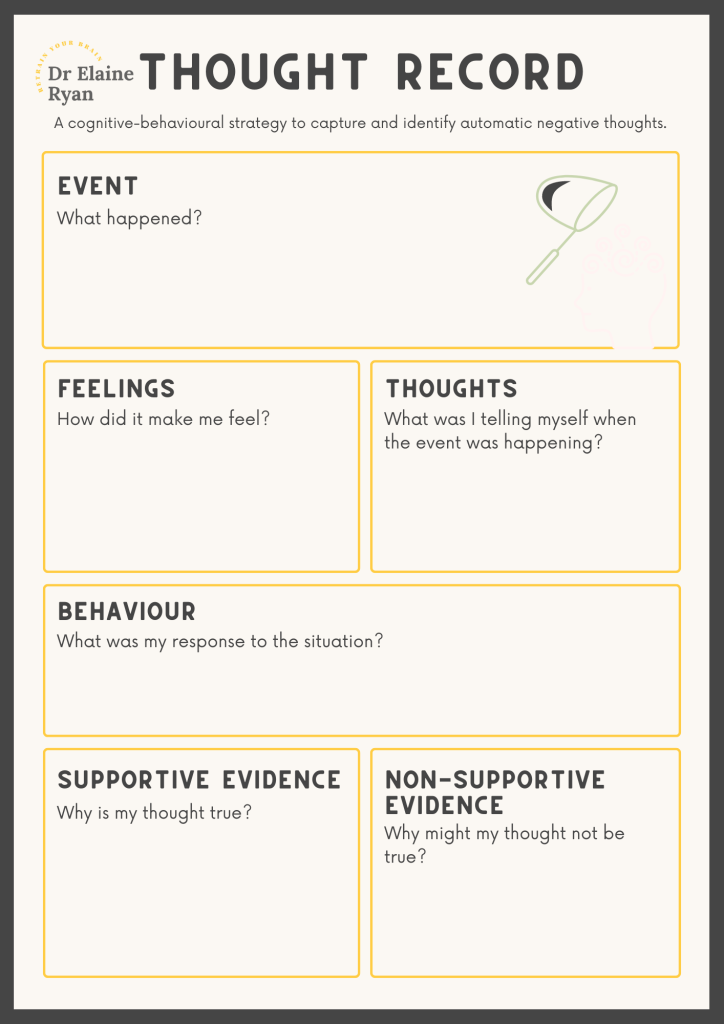

- Test those thoughts – using evidence, thought records and real?life experiments to see what’s actually true.

- Change behaviours that maintain anxiety – especially avoidance and “safety behaviours” (things you do to feel safe that ironically keep the fear alive). You can learn how to make your own behavioural experiments for anxiety here.

For example:

- Someone with panic might avoid exercise, in case a racing heart triggers a panic attack. In CBT, we’d slowly reintroduce gentle exercise while showing the difference between normal exertion and panic – so the heart racing no longer signals catastrophe.

- Someone with social anxiety might replay conversations for hours, convinced they sounded stupid. In CBT, we’d challenge those beliefs, look at realistic evidence, and plan graded “experiments” such as intentionally saying something small in a meeting and observing the actual response.

CBT is active and practical. You’ll have things to try between sessions, and we’ll review how they went. It’s not about “thinking positively”; it’s about thinking accurately and behaving in ways that reduce anxiety in the long term. I am going to take some time now and show you what CBT is like and give you some things to try to allow you to get a flavour of CBT.

Imagine Saoirse who has social anxiety and thinks, “If I speak in meetings, I’ll say something stupid, and everyone will think I’m a fool” This negative thought causes Saoirse to feel extremely anxious and avoid speaking up in meetings.

- Identifying Maladaptive Thought: Saoirse’s therapist helps her identify this automatic negative thought that triggers anxiety.

- Challenging the Thought: They work together to challenge the validity of this thought by asking questions like, “What evidence do you have that you will say something stupid?” and “Have there been times when you spoke in a meeting and things went well?”

- Reframing the Thought: Saoirse learns to reframe her thought to something more balanced, like, “I might feel nervous, but I can prepare and contribute meaningfully to the meeting.”

- Behavioural Change: With this new way of thinking, Saoirse gradually starts to participate in meetings. As she does this, she realizes that her fear of negative judgment was exaggerated, which reduces her anxiety over time.

By changing his maladaptive thinking, Saoirse changes her behaviour (participating in meetings) and her emotional state (reduced anxiety). I’ve make a quick video to explain how CBT works.

How CBT Works for Anxiety

The tenet of CBT is that your thoughts, not events, affect your feelings and actions. For example, if you have to give a speech, your fearful thoughts create anxiety, not the address. ; in other words, your thoughts can create anxiety. CBT helps you see the link between your thoughts and emotions and shows you how to change them.

CBT works for anxiety by addressing the distorted thinking patterns that contribute to your anxious feelings and behaviours. It focuses on identifying, challenging, and altering these negative thought patterns and replacing them with more realistic and balanced ones. Here’s how CBT helps in managing anxiety:

- Identifying Negative Thoughts:

- Example: Imagine you have a big presentation at work. Your automatic thought might be, “I’m going to mess this up, and everyone will think I’m incompetent.” In CBT, you learn to recognize this thought as a common trigger for anxiety.

- Challenging Negative Thoughts:

- Example: Your therapist might ask you to examine the evidence for and against your belief that you’ll mess up the presentation. You might realize that you’ve successfully delivered presentations before and received positive feedback, which challenges the initial negative thought.

- Changing Behaviour:

- Example: Instead of avoiding presentations out of fear, CBT encourages you to confront the situation. You might start with smaller tasks, like speaking up in meetings, gradually building confidence. Over time, this helps reduce anxiety around public speaking.

You can see in the image below a sample CBT thought record that you would typically use to record and change your thoughts and I have included the worksheet in PDF format for you to download.

Key Techniques Used in CBT for Anxiety

Several techniques are employed in CBT to help you manage anxiety:

Cognitive Restructuring:

- Example: Aisling often thinks, “If I don’t get everything perfect, I’ll fail.” In CBT, she learns to challenge this thought by considering more balanced perspectives, such as, “It’s okay to make mistakes; I can learn from them.” You can learn how to use cognitive restructuring techniques in this article.

Exposure Therapy:

- Example: Conor has a fear of flying. In session we gradually confront this fear by first looking at pictures of airplanes, then visiting an airport, and eventually taking a short flight. Each step helps reduce his anxiety.

Relaxation Techniques:

- Example: During stressful situations, Killian practices deep breathing exercises he learned in CBT. By focusing on his breath, he calms his mind and body, reducing his anxiety levels.

Behavioural Activation:

- Example: Aoife feels anxious about going out and often isolates herself. In session I encourage her to engage in activities she enjoys, like joining a book club. By doing so, she feels more accomplished and less anxious.

Benefits of CBT for Anxiety

CBT offers numerous benefits for those suffering from anxiety:

- Long-term Effectiveness: CBT provides you with tools and strategies they can use beyond the therapy sessions, promoting long-term management of anxiety. I always say in session that they whole idea of CBT is to make me redundant; you should get to a stage where you do not need your therapist and have the tools at your disposal.

- Skill-building: You learn practical skills to identify and challenge negative thoughts and manage their anxiety independently.

- Empowerment: By understanding the cognitive-behavioural model, clients feel more in control of their anxiety.

- Evidence-based: Numerous studies, including those by the American Psychological Association and the National Institute of Mental Health, support the effectiveness of CBT in treating anxiety.

It is a cost-effective treatment.

CBT is a cost-effective treatment option due to the structured nature of the model. It is a short-term model of therapy and has been shown to work, so in theory, you should not have to return and pay for more sessions. This makes it cost-effective if you have to pay for the therapy yourself or for employers or other bodies being billed for treatment.

Also, due to the nature of the model, it can be effectively delivered through self-help books, courses and online, not only adding to its cost-effectiveness but also giving the client more choice in how they wish to receive treatment.

It can be used to treat many types of anxiety disorders.

CBT is an accepted model of therapy for the different types of anxiety disorders, including

- GAD

- panic disorder

- social anxiety

Depending on your type of anxiety disorder, the model can be tailored to your needs. This is done through the homework that is part of CBT.

During homework, think of yourself as a scientist gathering evidence on your thought processes and behaviours before testing them and changing them.

The data you collect on your thoughts and behaviours will be unique to you and your type of anxiety disorder, and your therapist will then show you how to change your beliefs or design behavioural experiments that will fit you.

It can help people learn how to deal with their anxiety in the future.

When you fully understand what led to anxiety and, through behavioural experiments, see that you can handle situations that previously led to fear and anxiety, this gives you the confidence to manage stress-provoking problems in the future.

CBT can help you in other areas of your life.

Once you have gone through the process of CBT and understand how your thoughts and behaviours can either help or hinder you, this skill can be applied to many aspects of your life.

As a psychologist, I regularly use CBT not only to help people with anxiety but also to help improved their relationships or as a form of coaching to help with self-development.

The whole idea of CBT is to teach you to be your own therapist and make your therapist redundant. Once you have achieved this, you do not need to return and pay

If you are ready for therapy it is crucial that you not only find someone competent and trained in CBT but also a therapist that has extensive knowledge of anxiety and how to work within the model of CBT and apply it to anxiety.

Finding a qualified CBT therapist is crucial for effective treatment. Here are some tips to help you in your search:

- Check Credentials: Ensure the therapist is licensed and has specific training in CBT.

- Ask for Recommendations: Seek referrals from healthcare providers or trusted individuals.

- Research Experience: Look for therapists with experience in treating anxiety disorders.

- Initial Consultation: Schedule a consultation to discuss your concerns and gauge if the therapist’s approach aligns with your needs.

Additional Resources for Help

For further information and support, consider the following resources:

- BABCP: Provides a directory of CBT therapists

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH): Offers information on anxiety disorders and CBT.

In Practice: Another Quick Example of How to Apply CBT

Situation: You get invited to speak at a work event.

- Old Pattern:

- Thought: “I’ll definitely make a fool of myself.”

- Feeling: Fear/dread.

- Body: Racing heart, tense stomach (overactive amygdala).

- Behaviour: You find a reason to cancel or avoid.

- Using the Model:

- Identify & Challenge: “Is it certain I’ll fail? I’ve spoken up in meetings before without catastrophe.”

- Physiological Shift: Practice slow breathing for 1 minute, calming the fight-or-flight surge.

- New Behaviour: You decide to at least attend and share one brief comment.

- Scientific Backing: Studies show repeating this pattern weakens fear pathways and strengthens confidence pathways in the brain (neuroplasticity).

What to Expect in Anxiety Therapy With Me

Your First Session – Mapping Your Anxiety

The first session is a chance for you to tell your story at your own pace.

We’ll talk about:

- what you’re struggling with now – symptoms, triggers, how anxiety affects your life

- when you first remember anxiety showing up (for many people it goes back years)

- any previous help you’ve had (counselling, medication, courses) and what did / didn’t help

- your goals – what you’d like life to look like if anxiety was no longer in charge

I’ll ask some questions to get a clear picture, but there’s no interrogation and no pressure to share things you’re not ready to. Many people tell me the first session already feels relieving – it’s often the first time they’ve talked honestly about anxiety with someone who really gets it.

By the end of that first appointment, I’ll usually be able to say:

- what type(s) of anxiety you’re dealing with (e.g. panic disorder, GAD, social anxiety, health anxiety, or a mix)

- what patterns I see in your thoughts/behaviours

- an initial treatment plan and how CBT/counselling can help

You’re very welcome to ask questions about the process. Therapy is a partnership; you should feel comfortable with the plan.

Ongoing Sessions – Skills, Practice and Gradual Change

Most people start with weekly sessions. As things improve, we might move to fortnightly.

A typical session might include:

- checking in on how your week has been

- reviewing any anxiety spikes or difficult situations

- discussing how homework / experiments went

- teaching and practicing a new skill (e.g. a breathing technique, a way of responding to a particular thought, planning an exposure step)

- agreeing on a small, doable goal for the coming week

I often sketch out your “anxiety cycle” visually in session so you can see how it works – many clients find that incredibly helpful: “Oh, so when I avoid that situation, it actually confirms the fear… that’s why it’s stuck.”

We then systematically break that cycle:

- adjusting thoughts

- tweaking behaviours

- experimenting with new responses

- gradually facing feared situations

It’s normal for anxiety to rise a bit at points – especially when you’re facing things you’ve been avoiding. We’ll prepare for that and build in support. The whole point is that you’re not doing this alone or blindly; we’ll move step by step with plenty of safety nets.

How Long Does Treatment Take?

There’s no one answer, but to give you a realistic sense:

- for a single, focused anxiety problem (e.g. panic attacks, social anxiety, health anxiety) a structured CBT approach often takes around 8–15 sessions

- for more complex or long?standing anxiety, or when there are other difficulties (depression, trauma, OCD), treatment may take longer

We’ll review progress regularly. You’ll know therapy is working when:

- you can do things you used to avoid

- the intensity and frequency of anxiety drops

- even when anxiety shows up, you feel more confident managing it

- your life feels bigger again (more activities, less fear dictating choices)

Therapy isn’t meant to be endless. The aim is that you build a skill?set and confidence so that you no longer need me.

Medication

As a psychologist, I don’t prescribe, but I often work with clients who take meds concurrently. We’ll monitor how it’s going, and sometimes part of therapy is optimising that aspect (for instance, ensuring you’re not relying on a tranquilizer as a sole solution but using the space it gives you to practice therapy skills). If you want to taper off meds eventually, therapy can assist in providing coping tools to do so smoothly with your doctor’s guidance.

In Ireland, medication for anxiety is prescribed by medical doctors – usually your GP, and sometimes a psychiatrist – not by psychologists. For conditions like generalised anxiety disorder, the HSE notes that medicine is usually considered if psychological therapies and talk treatments have not helped enough.

Common options your GP might discuss include antidepressants such as SSRIs (for example sertraline, escitalopram, citalopram or fluoxetine) and sometimes SNRIs like venlafaxine or duloxetine. In certain cases, other medicines such as pregabalin may be used if SSRIs or SNRIs are not suitable, and benzodiazepines (like diazepam) may be prescribed very short?term during a severe spell of anxiety because of their addiction risk.

Decisions about whether to start, change or stop medication are always made between you and your GP or psychiatrist, taking into account your overall health, other medicines and possible side?effects. My role as a psychologist is to provide evidence?based therapy alongside this – I do not prescribe, but with your permission I’m happy to liaise with your doctor so that therapy and medication work together rather than in isolation.

How to Reach Out

If you’d like to discuss whether anxiety therapy with me is a good fit, you can:

- use the contact form on the Contact page

FAQs About Anxiety Treatment

Q: Do I need a GP referral to see you?

A: No. You can contact me directly. If you’re already under the care of a GP or psychiatrist, I’m happy to work alongside them. If I feel a medical review is needed (for example, if some symptoms need checking), I’ll say so and we can coordinate.

Q: I’ve tried counselling before and it didn’t help. Is this any different?

A: It can be. “Counselling” is a very broad term. CBT and structured anxiety treatment are more specific – we don’t just talk about how you feel; we also map the anxiety cycle and actively experiment with different ways of thinking and behaving. That said, your past experience matters – we’ll talk about what didn’t work before and make sure we do things differently this time. Sometimes previous therapy has lacked a clear focus on anxiety, or hasn’t included enough practical work between sessions. We’ll be very intentional about that.

Q: Will I have to do things that terrify me?

A: We won’t throw you in the deep end. Facing fears (through graded exposure) is part of effective anxiety treatment, but it’s done gradually and collaboratively. We’ll agree each step together. You’ll never be forced to do something you’ve strongly said no to. In fact, most people are surprised to find they feel more in control when they’re facing fears with a clear plan, rather than avoiding things and feeling controlled by anxiety.

Q: Can I do therapy if I’m already on medication?

A: Yes. Many of my clients are on medication prescribed by their GP or psychiatrist. Medication can reduce the intensity of anxiety enough to help you get more out of therapy. Over time, some people choose to reduce or stop medication with their doctor’s guidance once they’ve built strong CBT skills; others prefer to stay on a stable dose. We’ll work with whatever you and your doctor decide – therapy does not depend on being off medication.

Q: Is online therapy really as good as in-person?

A: For many anxiety problems, yes. Research comparing face?to?face CBT and therapist?supported online CBT shows similar improvements in anxiety symptoms when the treatment is delivered properly. What matters most is the quality of the therapeutic relationship and the work you do between sessions, not whether the room is physical or virtual. If we start online and you later decide you’d like to try an in?person session (and you can travel to Dublin), we can arrange that.

Q: What if I start therapy and decide it’s not for me?

A: You’re never trapped. You’re free to stop at any time. I do encourage people to give it a fair try (e.g. a few sessions), as anxiety often resists change at first and it can take a little while to feel the benefit. If at any point you feel the approach isn’t right for you, we’ll talk about it honestly. I can adjust what we’re doing, or if you prefer, help signpost you to other services that might suit you better. My priority is that you get the help you need, whether that ends up being with me or elsewhere.

What is Anxiety?

I’ll explain how this happens, and how it can be reversed, in more detail below. Anxiety is one of the most common mental health problems in the world. In Ireland, research undertaken by my former employer, Maynooth University, found that 42% of adults have a mental health disorder, with 7% having Generalised Anxiety Disorder. Further information and support can be found through HSE and Mental Health Ireland.

Normal versus Clinical Anxiety

Normal (situational) anxiety is a temporary response to stressors like an interview or an exam, it occurs in response to a specific situation and then goes away. This kind of anxiety is adaptive – it can sharpen your focus and keep you safe.

Anxiety becomes clinical anxiety (an anxiety disorder), when it is excessive, persistent, and interferes with daily life and one of the first things that people notice, is that they feel different, their body feels different. People often describe it as feeling “on edge all the time”, “switched on”, or “not myself anymore”. You may notice:

- your behaviour changes (avoiding things, needing reassurance, not doing what you used to do)

- your body feels different (heart, breathing, stomach, sleep)

- your thoughts feel different (constant “what ifs”)

Evolution of Anxiety

To explain why anxiety is so common now, I find it helpful to borrow an idea from neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky, who wrote Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers. The basic point is simple but powerful:

Our bodies are using a very old stress system to cope with a very new kind of life.

Immediate Threats vs Modern Worries

Imagine an antelope on the African plains.

- A lion appears ? the antelope’s body floods with stress hormones ? it runs for its life.

- If it escapes, the threat is over ? its body calms down ? it goes back to grazing.

The stress response switches on when there is a real, immediate threat, and then off when the threat is gone. Psychologists call this an immediate-return environment – you act, and you get feedback quickly. You either survive the lion or you don’t. There’s no lying awake at 3am thinking, “What if a lion comes in six months?”

Now compare that to modern human life.

Most of our “threats” are not things happening in front of us right now; they’re ideas about the future:

- What if I can’t pay the mortgage next year?

- What if this pain is something serious?

- What if my relationship breaks down?

- What if I lose my job?

You can’t run away from “What if I get cancer in 10 years?” or “What if the kids are not okay?” So you end up with a stress response that activates, but never gets a clean signal that the danger has passed. This is what Sapolsky means when he says wild animals don’t get ulcers – they don’t sit around thinking their way into chronic stress. We do.

We now live in what researchers call a delayed-return environment:

- You work hard today, but you only find out weeks or months later if it paid off.

- You save money for a pension you won’t see for decades.

- You invest emotionally in relationships not knowing how they’ll turn out.

Your body, however, is still wired for the immediate-return world – lions, storms, sudden danger. It reacts to thoughts about future problems as if the lion is in the room right now.

Why This Creates Chronic Anxiety

This mismatch between an old brain and a new world is at the heart of a lot of modern anxiety.

In the environment our nervous system evolved for, stress and anxiety were mostly:

- short-term – minutes or hours

- specific – a clear danger in front of you

- resolvable – you did something (run, hide, fight), and then it was over

In our world, a lot of stress is:

- long-term – days, months, years

- vague – “life”, “the future”, “my health”, “money”

- not easily resolved – there is no single action that “finishes” the problem

So your brain keeps scanning and scanning for threats it can’t fully solve. Your autonomic nervous system (the fight-or-flight system we’ll come to next) is being asked to respond not to a lion in the field, but to:

- an email from your boss

- a bank statement

- a news headline

- a memory of something you regret

- or a “what if…?” thought at bedtime.

The body doesn’t really distinguish between “There is a real danger right now” and “I am imagining a danger later”. Both can trigger:

- racing heart

- knots in your stomach

- tense muscles

- shaky, wired feelings

- trouble sleeping

The crucial difference is that with lions and storms, the danger ends. With mortgages, health worries and relationship fears, there is often no clear end point. That’s how we move from short-term fear (which is healthy and protective) to chronic anxiety (which is exhausting and miserable).

What This Means for You

Many people I work with say things like:

- “I must be weak; other people cope.”

- “There’s something wrong with my brain.”

- “I’m overreacting – there’s nothing to be anxious about.”

When we put it in this context, a different picture emerges:

You’re a human with an ancient threat system, living in a world that is constantly poking it.

Your nervous system is doing exactly what it evolved to do – it’s just doing it too often and for problems you can’t resolve immediately.

We can’t go back to living like antelopes, but we can teach your very old survival system how to live more comfortably in the modern world. The first step is to understand how that system actually works in your body.

Anxiety Symptoms

One of the first things people notice is that their body feels different. Many end up at A&E or with their GP convinced something is wrong with their heart, lungs or brain.

As a doctor of psychology who has personally experienced both anxiety and panic, I know how frightening these symptoms can feel. This section will show you why they happen and why, once your GP has checked you, they are usually uncomfortable but not dangerous.

Important: If you notice any new or worrying physical symptom, always talk to your GP first. Once serious medical causes have been ruled out, you can feel more confident that anxiety is behind what you’re feeling.

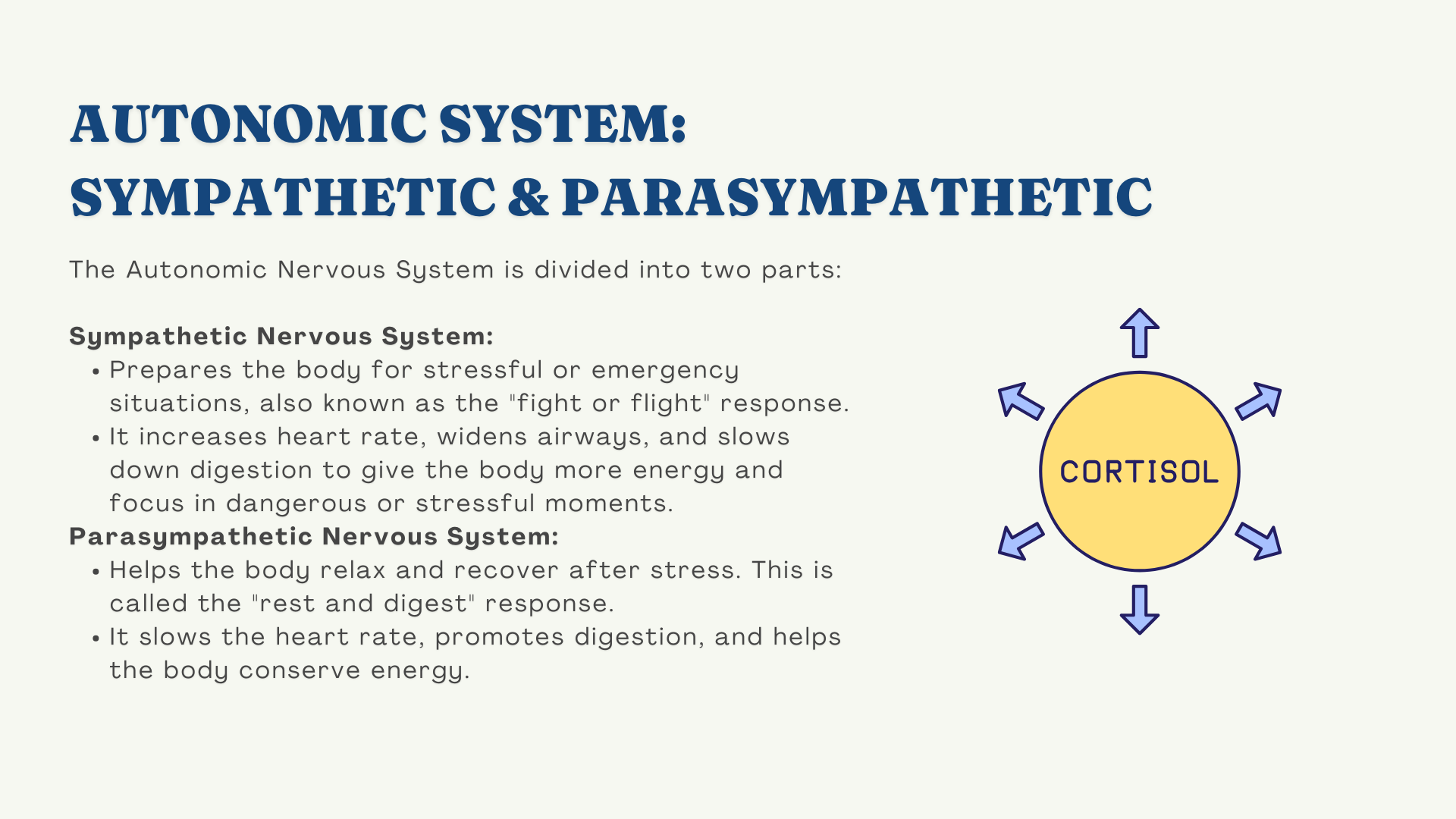

Your Autonomic Nervous System: The Engine Behind Your Anxiety Symptoms

The stress response is controlled by a system in your body called the autonomic nervous system (ANS). Autonomic simply means automatic – it runs without you having to think about it.

It has two main branches:

- Sympathetic nervous system (SNS) – your fight-or-flight system, the “accelerator”

- Parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) – your rest-and-digest system, the “brake”

You can think of it like driving a car:

- Press the accelerator (SNS) ? heart and breathing speed up, muscles tense, senses sharpen

- Press the brake (PNS) ? heart and breathing slow down, digestion resumes, you can relax

Most of the time, your body is gently balancing these two. When there’s a genuine threat, the accelerator takes over. When the threat passes, the brake comes back on.

In anxiety, the problem is not that the system is broken – it’s that the accelerator is being pressed too often or too hard, usually by worries and “what if” thoughts rather than actual lions.

What Happens When Your Stress System Turns On

Very briefly, here’s what happens when your brain thinks there might be danger:

- A part of your brain called the amygdala (your “smoke alarm”) detects a possible threat – this can be something real in front of you, or a thought, image, memory or bodily sensation. Learn more about your amygdala and its role in anxiety.

- The amygdala sends a signal down to your body:“We might be in trouble – get ready!”

- Your sympathetic nervous system (SNS) switches on. This triggers the release of adrenaline and other stress hormones into your bloodstream.

- Adrenaline then causes a whole cascade of physical changes – very fast – to prepare you to fight or run:

- heart beats faster and harder

- breathing speeds up

- muscles tense

- blood is redirected away from digestion and towards your limbs

- senses sharpen

If you were facing a bull in a field, this reaction would be perfect. In modern life, it often gets switched on by:

- an email from your boss

- a bank statement

- a strange sensation in your chest

- a memory of something embarrassing

- a “what if…?” thought at 3am

Your body reacts as if there’s a lion, when in reality you’re sitting on the sofa or lying in bed. This is why your symptoms feel so out of proportion.

Common Physical Symptoms (Head to Toe)

Rather than seeing your symptoms as random or scary, I want you to see how each one has a survival purpose.

You don’t need to memorise this – just notice how your experience fits.

Racing, pounding heart / palpitations / chest pain

Your heart is pumping faster to get blood to your big muscles in case you need to run or fight. That heavy thump in your chest feels frightening, but if your heart is healthy, it is simply doing its job in fight-or-flight mode. Muscle tension and breathing changes can also cause sharp or tight chest pain.

Shortness of breath, tight chest, sighing, dizziness

You may start breathing faster than you need (hyperventilating) without realising. This changes the balance of oxygen and carbon dioxide in your blood, which can cause:

- light-headedness

- tingling in fingers, lips or face

- a feeling of “air hunger” or not getting a proper breath

It’s very uncomfortable, but your body is actually getting enough oxygen – it’s the balance that’s off. Slowing your breathing can help.

Muscle tension, shaking, aches and pains

Muscles tighten to get you ready for action – think of a sprinter on the starting blocks. If you never actually run, that tension hangs around as:

- tight shoulders and jaw

- headaches and back pain

- trembling or shaking from all the pent-up energy

Stomach and bowels (butterflies, nausea, IBS)

Digestion is not a priority in an emergency. Blood is redirected away from your gut. This can give you:

- nausea, cramps, “knots”, butterflies

- indigestion, reflux or bloating

- diarrhoea or urgent trips to the loo

- or, for some people, constipation

It’s the same system that would have helped your ancestors “lighten the load” to run faster.

Tingling, numbness, hot flushes, chills

Changes in blood flow and breathing can cause:

- pins and needles or numbness in hands, feet or face

- sudden hot flushes or blushing

- cold hands, shivers or goosebumps

These are normal effects of adrenaline, even though they can feel very strange.

Sight, hearing and feeling “unreal”

When your system is on high alert, your senses sharpen. Lights can feel too bright, sounds too loud. Some people get “tunnel vision” or a sense of being detached or “not quite here”. It’s your brain in full scanning mode, not proof that you’re losing your mind.

Sleep and restlessness

Stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol keep your system revved up. Useful if you need to stay awake to watch for danger; useless when you’re trying to sleep before work. This is why anxiety and insomnia so often travel together.

For a more detailed head-to-toe list of symptoms, see my dedicated Anxiety Symptoms page.

Emotional, Cognitive and Behavioural Symptoms

Anxiety doesn’t just affect your body. It affects your thoughts, emotions and behaviour too.

Emotional and thinking symptoms

- constant “what if?” worry

- fear that something bad is about to happen

- feeling on edge, irritable, or easily startled

- difficulty concentrating or feeling mentally foggy

Behavioural symptoms

- avoidance (not driving, not going to certain places, cancelling plans)

- seeking reassurance (“Are you sure I’ll be okay?”, Googling symptoms)

- safety behaviours (sitting near exits, carrying “just in case” items, always needing someone with you)

These responses make sense in the short term – they reduce anxiety quickly – but in the long term they can keep anxiety going, which we’ll come back to.

| Symptom | Sympathetic | Parasympathetic |

|---|---|---|

| Heart | Heart beats faster | Heart rate slows down |

| Coronary blood vessels | Dilates | Constrict |

| Lungs | Bronchial muscles relax | Constrict |

| Eyes | Pupils dilate | Pupils constrict |

| Sweat glands | Increased sweating | No effect |

| Salivary Glands | Dry mouth | Watery |

| Bladder | Relaxes bladder | Constrict |

| Digestion | Decreased activity | Increased activity |

| Mental | Increased alertness | None |

| Endocrine Pancreas | Inhibits insulin | Stimulates insulin |

| Kidneys | Decreased urine | Increased urine |

You are normally not aware of the operating of the autonomic nervous system, ANS. It works away, in the background, away from your conscious thought. It works with no effort on your part, like a reflex, adapting and responding to your immediate environment.

It is useful to understand how it works, if you want to understand anxiety and the symptoms that you experience You may be more familiar with the sympathetic nervous system, being called, “fight or flight.” It activates when we perceive we are in some sort of danger.

Example: If, late at night, you see a crowd of young teenagers coming toward you. They are loud and not familiar to you. This scenario might activate the SNS to prepare you to either run away or stand and face whatever happens. You are getting prepared for danger.

Activation of the sympathetic nervous system

- Release of adrenaline and noradrenaline

- Increase heart rate and blood pressure

- Increases blood flow to skeletal muscles

- Inhibits digestive functioning

When the young teenagers come closer and you see they are members of a local community, collecting for “bob – a – job” week, you immediately relax.

You do not consciously decide to relax, you relax as your parasympathetic nervous is activated – rest and digest.

Parasympathetic nervous system activation

- Lowers heart rate, breathing and blood pressure

Let me explain in more detail.

When we are relaxed and ready to kick back and unwind from our day, the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) enables us to do this, by relaxing our body, slowing down the heart rate and blood pressure.

When this happens we can easily relax into our favourite armchair and feel content. This is why some people refer to the PNS as the rest and digest system. Our body slows down and is able to concentrate on digesting our dinner and the removal of waste from the body.

This is not how we want to feel when meeting a bull, as we are not in a state to deal with it.

This is the beauty of the the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) (also know as fight or flight), it takes control of everything you need in the blink of an eye.

One second you are relaxed and content, and the next your heart is pounding out of your chest and you are no longer in that sleepy relaxed state. You are wide awake.

Does this sound familiar? Exactly like panic attack symptoms? Often you can feel ok, and then, out of the blue, your chest hurts, your heart is pounding.

With anxiety, you may have chest pain, difficulty relaxing or sleeping, your mind is racing and you have tummy troubles. With panic attacks, you may struggle to breathe, be sweating, shaking, and think you might die.

Although distressing, it is just your autonomic nervous system thinking that it has detected a threat and activates your SNS to help you out.

Think of your brain as constantly scanning wherever you are for possible danger. Once it detects something, anything, that might cause your harm, it protects you by activating the SNS when you need to be alert and ready to take action.

- Once this happens, your mind is sharper, you become more focused.

- Your bowels and bladder can empty making you lighter and able to run or fight.

- Your senses and vision are no longer sleepy, but sharp and taking in more information.

- Blood gets diverted to your heart to help it pump faster

It then activates the PNS (the rest and digest) when the danger has passed to allow you to relax.

Where do you feel anxious?

Different parts of your brain, result in different experiences of anxiety.

Anxious for no reason

In the same situations

In thoughts and worries

You were not born anxious

You had to learn to be anxious

Your brain is captain of your ship. And more than likely, you have never read the instruction manual. This instruction manual is very important, otherwise your brain may be steering you places that you don’t want to go. To continue the metaphor, if you feel you are out at sea with your anxiety, and that you have no control, it is crucial that you understand your brain, as it is here, that you gain understanding, and eventually, control.

Dr Elaine Ryan

Your 3 brains

It is important to understand all three as they may be working together to give you anxiety.

Note: Paul MacLean introduced the idea of The Triune Brain, and I refer to it here as it is easier to understand that the biological names; you’ve probably come across other clinicians or writers talking about lizard brain, rather than calling it the limbic system.

Your Reptilian Brain

This was the first part of your brain to evolve.

It manages things that you don’t have to think about, unconscious processes such as breathing, temperature and the fight or flight response (for those of you that have panic attacks, you have probably already read about the stress response.)

This is your survival instinct. It always watches out for you, but can over react to day to day things. Your reptilian brain was the first part of your brain to evolve. It is very basic, it doesn’t think, and acts on an instinctual basis.

Can it kill me or will I kill it?

Although it can get you into trouble in terms of anxiety, it is a very useful instinct to have. If you are in danger, your brain reacts instantly, rather than relying on the slower, more intelligent part of your brain, where you would have to stop and think what to do. There is not time to weigh up all your options and decide the appropriate course of action if you have just stepped out in front of a bus.

This part of your brain is always on guard for you, even though you are not aware of it. Everywhere you go, it keeps an eye on potential danger. It regulates things that you do not have to even think about, like your heart rate, and the fight or flight response. It can however, protect you a little too much, as it really can’t tell the difference between a real danger or you just mulling over a real danger in your head.

In order to recover from anxiety, that occurs for no reason, you have to learn to calm down your instinctual reactions.

What does it feel like?

Or another example would be the intense physical feelings you get when watching a scary movie.

You react to the movie as if it where real.

This primitive part of your brain really can’t tell the difference.

Your reactions to the scary movie in terms of physical sensations, are down to the primitive part of your brain.

If you avoid scary movies in the future or think about the movie later, in the cold light of day, and still feel some fear, this is to do with other parts of your brain taking over and I shall talk about this now in terms of your mammalian brain.

Important Points to note

Your reptilian brain reacts to dangers, that are not really there. Your imagined dangers, your worries.

Your reptilian brain reacts without thinking, but then doesn’t do much else. On it’s own, its okay.

But when this interacts with your mammalian brain, this 2nd part of the brain can start to attach emotions. It remembers your fear.

Your mammalian brain

Like the reptilian brain, these emotional responses occur without any effort on your part, outside of your control.

They occur automatically.

This can help to explain why you feel anxious for no reason, giving for example a presentation, driving your car, or just out with friends. It has a lot to do with how your brain attaches emotion to certain memories

Your mammalian brain is better know as The Limbic system or your feeling brain

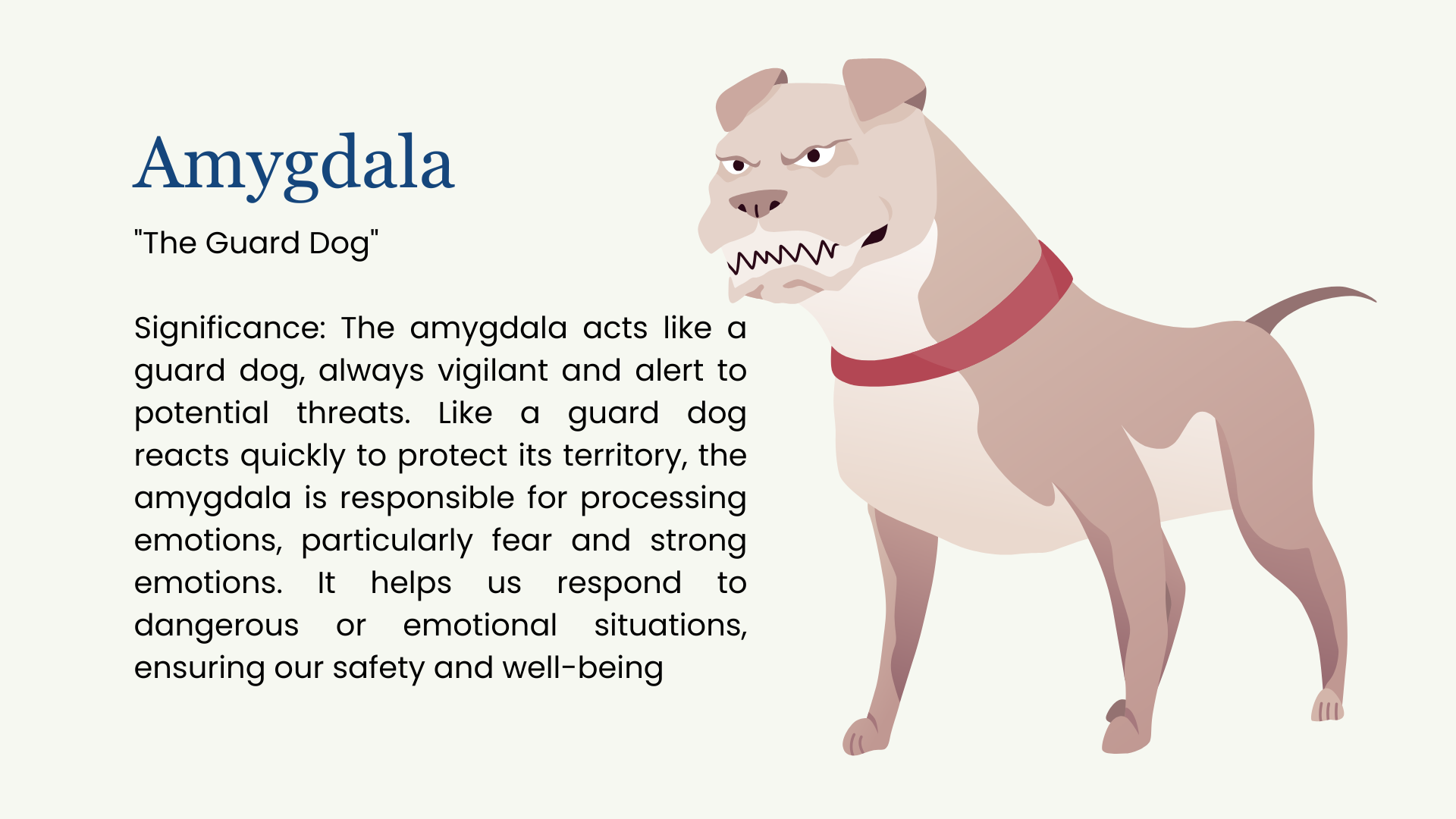

Your mammalian brain includes the amygdala, which is fundamental to understanding and treating anxiety.

The amygdala is left out of many treatment models.

If you have tried things in the past to help with anxiety and think that ‘it failed,’ take heart, you maybe didn’t have the right tools.

You will have read previously (or if not, go back and read it now ) that your reptilian brain protects you from the basis of it’s survival instinct.

Your mammalian brain can do quite a bit more, in that it has emotions. Not only that, it can attach feelings to what has happened.

For example, say you had a bad time with your boss and had difficulty getting through a presentation at work.

Your mammalian brain can attach the feeling (maybe embarrassment, stress, anger or panic ) to the event; your boss and the presentation.

It can do more than that, it can form emotional memories. Now when you recall your boss or the presentation and are telling people about your bad experience, you can feel it too.

If that occurs again and again, your brain is very quick to learn, and the next time you give a presentation in front of your boss, images and feelings, drawn from your emotional memory, are there for you. You panic!

You will know that your reptilian brain produces the fight or flight response. ‘Will it kill me, or do I kill it?’

This is such a primitive part of your brain, but gets activated now that your brain has matched ‘boss’ ‘presentation’ and ‘fear’ together, but it is really not helpful to have such a strong reaction each time you have to do a presentation in front of your boss.

Neuroscience points the way, letting you know that you can ‘unmatch’ this, or learn a different way for your brain to behave.If this is currently happening to you, it is just your brain.

Your mammalian brain is non verbal, it speaks to you by releasing chemicals.In order to fully recover from anxiety, you need to know what your brain does with this. How it learns, and that is more to do with your rational, intelligent brain.

Your thinking brain

Unfortunately, it is also responsible for a large amount of unnecessary suffering, depending on how you use your brain.

If you think a lot, plan for the worst case scenario; you might get stuck in certain thought patterns. Maybe you keep going over situations that have occurred in the past, or that might occur in the future, you need to look here.

If you have tried to get over anxiety or panic before and didn’t succeed, it might have been that you just tackled one of the above areas.You need to Retrain Your Brain to encourage a different style of learning, and to decrease the things that are keeping you anxious.

This is the brain that most of you will associate as being your own mind or your brain.

Your thinking brain is conscious.That said, you would think that it is under your control, but for many of you, it can feel that it has a mind of its own.

I am going back to the example I used when I was telling you about your mammalian brain – where you got anxious during a presentation with your boss. (, if you haven’t already done so.)

If you immediately forgot about the presentation, everything is well and good in your world. But this is not the normal response for your thinking brain.

Your thinking brain is intelligent, much more so than your reptilian (which is instinctual, gets you ready to fight your boss), and your mammalian (which stores your bad feelings with the memory of your boss and the presentation.)

Your thinking brain searches for meaning. It will desperately try to make sense of what happened at the presentation and fuel your thought processes to look for answers.

Was I nervous before I went in? What happened? It will also allow you to tell your friends about it, and/or and go over and over it again in your mind and feel the anxiety all over again.

Your 3 brains in action

Your thinking brain, rather than being in control, can feel like it is at the mercy of your reptilian and mammalian brain, as it cannot rationalise what has happened.

Reptilian Brain: gave you your fight or flight response

Mammalian Brain: allowed you to attach the fear and anxiety to the memory

Thinking Brain: now worries about it happening again, and you actually start to create, not only a learning curve, but anticipatory anxiety.

You are not aware of it, but you are forming a habit in your brain as your brain assembles all of this information together.

You are, in fact, forming a neural pathway (a network) in your brain connecting all of these things together. Unfortunately, it is an anxiety based learning that is forming in your brain.

Retrain Your Brain

There are a few less understood things that are important to understand if you want to get rid of anxiety.

How your brain learns and,

the function of automatic processes

What are you teaching your brain?

Your anxious brain

Your stress and relaxation response

Reversing your anxiety in your brain

Retrain Your Brain®

Find the root cause of your anxiety.

Retrain Your Brain®

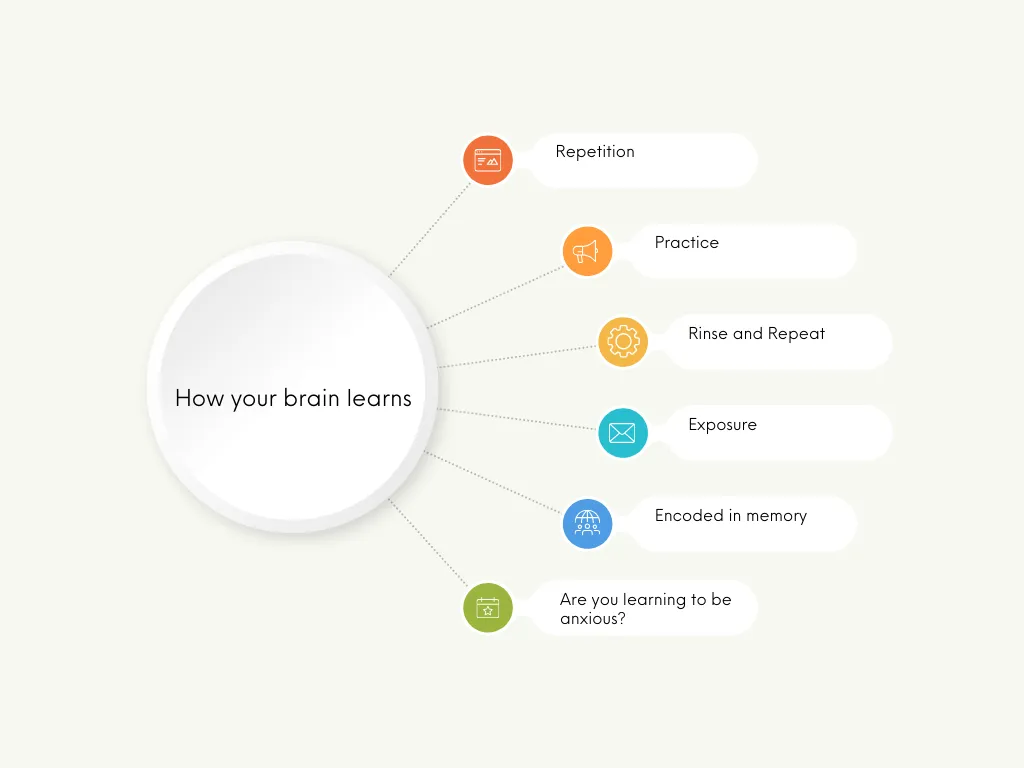

How your brain learns

Your brain

You can only do one thing at a time. If you don’t believe me, try this:

Count from one to ten in your head while you are reading what I am writing. You struggle.

You will struggle more if I tell you to stop reading, count to ten in your head, and recite the alphabet backwards at the same time.

Could you do it? No.

Your brain cannot actively process and give your full attention to more than one thing at a time.

You will of course, be able to do more than one thing at a time, we all multi-task. To be able to do this, your brain has to learn how to make most of the things that you do, automatic.

This is where you can run into trouble, as you may well have automatic processes that not only explain your anxiety, but also keep you anxious.

Due to the nature of these automatic processes, you will be repeating them all the time.

Your brain and automatic processes

When you paid attention to spelling and reading in school, with practice, it became real – you are reading this page.

Not only can you read it without trying, you can also understand it.

You may not know what is happening in your brain to allow you to read and understand, you just know you understand. It became automatic.

It became real.

When you pay attention to something, your brain learns by creating neural pathways or connections. You can think of these pathways as building blocks. The building blocks for reading this page started when you were 4 or 5 years old.

Practicing reading built up and strengthened the building blocks until now you can read this page with no difficulty. Everything to do with reading, spelling and understanding is stored in your brain

The more you practiced, the stronger the association became, until your practice paid off; reading became automatic. Practice makes perfect.

It is the same with anxiety; everything to do with anxiety will have its own neural pathways (building blocks) in your brain.

It is not the anxiety that is the problem, but how you habitually think, and how you habitually react, that creates problems in your life.

What are you teaching your brain?

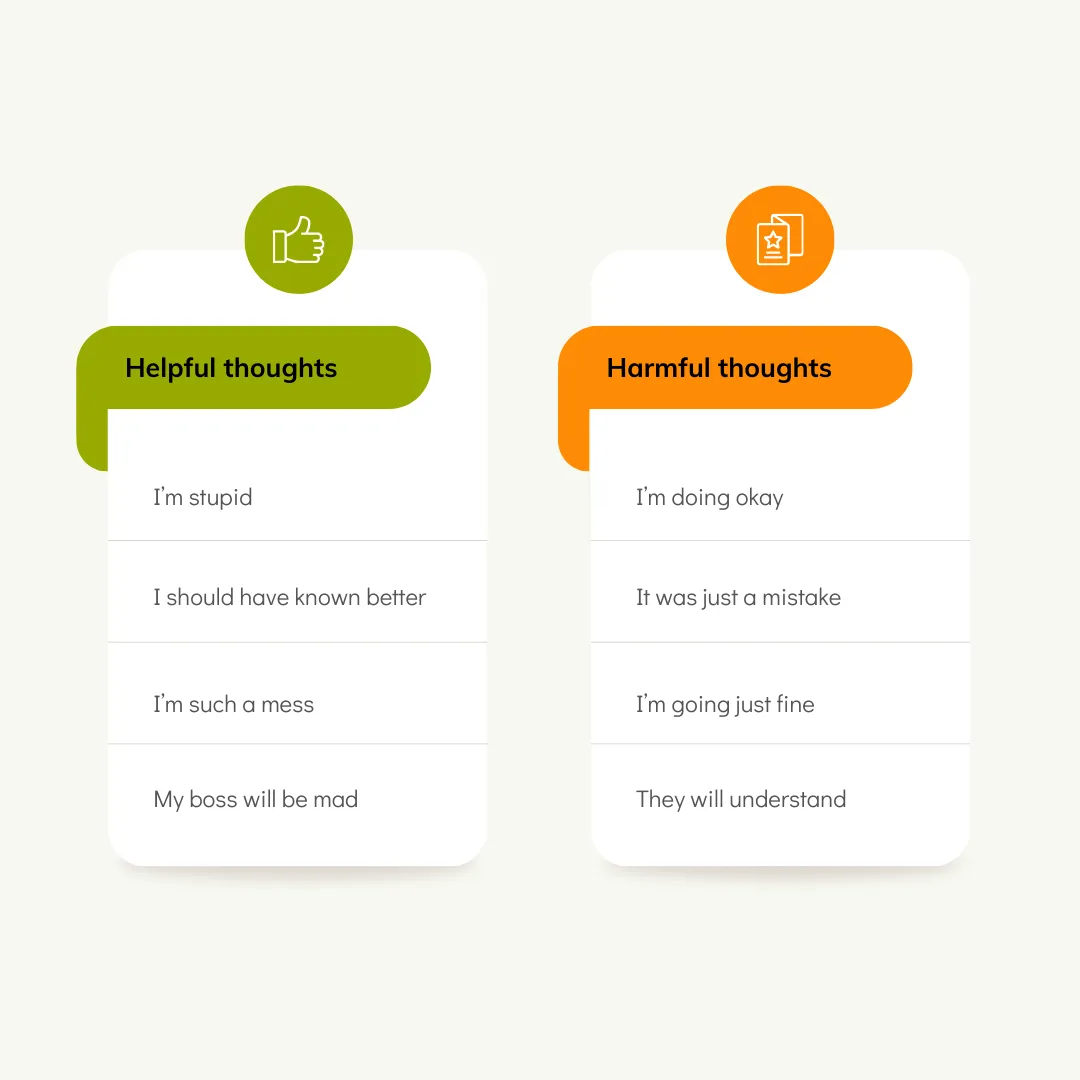

Are your thoughts helpful to you or are your thoughts harmful to you?

If you discover you are your own cheerleader, you can stop reading.

If you are like the rest of us (myself included), you may well have found that your thoughts do not help you out all the time

For example: You are late for work and it will take you one hour to get there. If you accept this situation and are nice and calm, you might enjoy the hours journey. More than likely you might be upset, annoyed, or giving out to yourself inside your head, “I should have got up earlier, “I should have taken another route”, and you may feel anxious when stuck in traffic.

These thoughts are related to how you respond to what is actually happening: you are late for work. Being late for work in itself, cannot cause anxiety. How you respond; can.

Unfortunately they may be part of a well-trodden path in your brain, sort of like a script, or a switch that turns on, giving you:

- Negative self talk;

- Feelings of anxiety or anger;

- Worry about what will happen.

If this is how you usually react, this well-trodden path in your brain gives you stress, automatically.

These ‘pathways or connections’ that become automatic, can be very powerful: you can slip back into the anxiety habit and not know why.

It’s why organizations, schools and the emergency services run drills, over and over again. In a crisis, they don’t think. They do what they have been trained to do, what has been drilled to become automatic. They have a well-trodden automatic path that allows them to respond without thinking.

Your anxiety has become a well-trodden path, always available to you in certain (or maybe all) situations.

Your habitual thoughts and reactions may have taught your brain to be anxious. Once taught, these habitual thoughts and reactions make sure that you stay anxious.

You were not born anxious.

Your brain is primed to pay more attention to negative experiences rather than positive ones, as the negative ones may harm you.

As I said before, it is not the anxiety that is the problem but how you think about it and how you respond to it.

If in the above example, you worry about being late, and feel stressed, anxious or angry at being stuck in traffic, your brain is alert to this negative situation.

The dangers that your brain is responding to, are no longer life-or-death situations, but day-to- day experiences.

Deadlines;

Money worries;

Work/school;

Relationships.

All the ‘self-talk’ that goes on inside your head.

Your anxious brain is always on the look out for possible ‘danger.’ When there is no real danger there, your mind takes over, and worries, races; you expect the worse.

Physical symptoms, maybe even panic attacks develop. The pathway in your brain for anxiety becomes stronger. It is able to connect your worries with the physical symptoms in your body.

If you worry about a meeting, or dread going somewhere in case you have anxiety, your brain pays attention to this. New pathways are created relating to anxiety. Now if someone mentions the ‘meeting’ or the place ‘you dread going’ your anxiety pathway is activated, and your brain can give you everything related to anxiety.

Your worries, the physical symptoms, they all appear automatically. Just like reading this page.

You can now feel anxiety in many situations and not know why.

You have your own automatic pilot for anxiety.

What your brain pays attention to becomes real.

You are now living with an automatic stress response

What is a stress response and a relaxation response, and why they are important?

The following is a copy of a webinar, even though the webinar was on panic attacks, and I would recommend watching it to answer some questions about the stress response.

The course I refer to in the video

The stress response and nervous system is covered in detail about, but I shall give another example as a refresher. Let’s take an example of sitting in your favourite armchair after dinner.

If your brain and body is working well for you, it will do the following:

Your rest and digest nervous system will give you a relaxation response, to relax your body and help you to digest your food. You feel comfortable and relaxed. The relaxation response is what helps you to kick back and unwind from your day.

Suddenly there is an extremely loud bang in the other room.

Your brain takes over and gives you a stress response to make you feel alert and able to move quickly to see what has happened.

One second you are almost asleep and the next your heart is pounding and you are in the other room. Does that sound familiar? One second you feel ok and the next you feel stress or anxiety?

You see that your dog knocked over a stool and you calmly walk back to your favorite armchair.

Soon your heart rate has slowed down and you are feeling comfortable again, as your nervous system has replaced the stress response with a relaxation response (rest and digest.) You fall asleep.

This is how our nervous system should work for us, giving us stress when we need it, and relaxation at other times. However, if you experience any form of stress, you will be feeling the effects of the stress response in many situations where you do not need to.

You may find it difficult to kick back and relax, and feel the benefits of the relaxation response as you are on constant high alert – getting the stress response too often when it is not needed.

Your brain is primed for stress and associates the small things in life with stress. Each time you encounter them, your brain gives you stress.

I would like to reassure you that science shows that you can change the way your brain is working for you. Your brain changes during your life depending on the thoughts that you have and how you react to all the different experiences that you encounter in your life.

In order to reverse your anxiety, you need to Retrain Your Brain®

I do not want to fill your head with miracle cures; rather I want to offer a no nonsense, practical explanation to why you feel stressed, burned out, and anxious.

I want to show you how to pay attention differently. To give you control over what is happening. To help you to create new building blocks in your brain. Ones that are more helpful to you. If you want to step out of automatic pilot mode, say goodbye to your unwelcome anxiety and take control of what is happening, then I invite you to have a look at my Retrain Your Brain Program.

Recap. So far we have discussed anxiety, understood the symptoms and different ways it can occur. Now, I want to talk about the different types. If you end up meeting someone like myself, a psychologist, we would conduct an assessment, not just to tell you whether or not you have anxiety, but also to tell you what type you have, and I shall outline the main anxiety disorders below.

Types of Anxiety Disorders

Generalised Anxiety Disorder GAD

Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD) is a common mental health condition characterised by persistent and excessive worry about a wide range of everyday things. You can learn more about the symptoms, causes, and treatments for GAD on my dedicated Generalised Anxiety Disorder page.

- Worries out of proportion to the situation

- It’s very difficult to control your worry even though you know it is not helping

- Worry affects many aspects of your life, such as how you cope in work, your relationships and your health.

- You probably have physical symptoms, feeling restless but also tired, hence the expressions ‘tired but wired.’

Panic Disorder

Panic disorder is more than having a panic attack, with panic disorder you have repeated attacks over an extended period of time and that interfere with your life.

During a panic attack, you might experience:

- Racing heart

- Chest pain

- Shortness of breath

- Feeling like you can’t catch your breath

- Choking or smothering sensation

- Dizziness

- Lightheaded

- Shaky

- Sweating or chills

- Feeling sick, tummy upset

- Scared that you are going to lose control and ‘go crazy.’

Example. You’re driving to work, something you have done many times before, when suddenly, your heart starts pounding, you feel dizzy, and your chest tightens. This is terrifying, especially when you are in control of a car, or on the M25 going into London! You might feel like you’re having a heart attack or that you’re about to lose control. This is what a panic attack can feel like. Learn about the differences between anxiety and panic attacks.

People with panic disorder often worry about having more panic attacks and may start to avoid situations where they fear an attack might happen. In the example I used above, it is understandable if the person tries to avoid driving.

Learn more about Panic Disorder, its causes, and effective treatments on my Panic Disorder page

Phobias

A phobia is much more than not liking something. For example, I am much better now with spiders, I am not overly keen on them, but don’t fly into a tailspin if I see one. In my professional life, I have worked with a client who moved house as they could not find a spider. That is a, albeit, an insane, phobia. A phobia is an intense, irrational fear of a specific object or situation. People with phobias often go to great lengths to avoid their triggers, as with my client, which can significantly disrupt their lives.

Common types of phobias:

Specific Phobia

where you are afraid of a specific object or situations, for example, blood, animals, flying.

Agoraphobia

Fear of situations where escape might be difficult or help unavailable, such as using public transportation, being in open spaces, being in enclosed spaces, standing in line, or being in a crowd. This often occurs with panic disorder.

Social Anxiety Disorder

Social anxiety, also known as social phobia, is more than just being shy. It’s an intense fear of social situations where you might be judged or negatively evaluated. This can lead to avoiding social gatherings, public speaking, or even everyday interactions like making phone calls or eating in public. Learning how to overcome social anxiety can greatly improve your quality of life.

Example: Imagine you’re at a party. You feel like all eyes are on you, judging your every move. Your heart races, your palms sweat, and you just want to disappear. This is a glimpse into what it’s like to live with social anxiety. It can make it incredibly difficult to connect with others and enjoy social events.

Learn more about Social Anxiety Disorder

Separation Anxiety Disorder

While often associated with children, separation anxiety can also affect adults. It involves excessive fear or anxiety about being separated from people you’re attached to. This can lead to constant worry, clinginess, and difficulty being alone or away from loved ones.

Example: An adult with separation anxiety might experience intense anxiety when their partner goes on a business trip. They might have persistent worries about something terrible happening, struggle with sleep, and find it challenging to function until their loved one returns.

Selective Mutism

Often first noticed in childhood, selective mutism involves a consistent inability to speak in specific social situations, despite being able to speak in other settings. This can significantly impact a child’s school performance, social development, and overall well-being.

Example: A child with selective mutism might speak freely at home with their family but remain completely silent at school, even when asked direct questions by teachers or classmates.

The HSE provides information on selective mutism and how to get a diagnosis.

Less Common Anxiety Disorders

In addition to the common types discussed above, there are other anxiety disorders that you might encounter:

- Substance/Medication-Induced Anxiety Disorder: Anxiety caused by the use of substances (e.g., alcohol, drugs) or withdrawal from them.

- Anxiety Disorder Due to Another Medical Condition: Anxiety directly caused by a medical condition, such as hyperthyroidism, heart problems, or neurological conditions.

- Other Specified Anxiety Disorder and Unspecified Anxiety Disorder: These are categories used when someone experiences significant anxiety that causes distress or impairment but doesn’t fully meet the criteria for any of the specific anxiety disorders.

Each anxiety disorder has distinct triggers and patterns, but all can be addressed by understanding their underlying thought–feeling–behaviour cycles.

Cause of Anxiety: Understand the Factors

Anxiety typically arises from a mix of factors:

Thought Patterns

Negative thinking, catastrophising, mind-reading.Learned worry behaviours from caregivers or past experiences. Constantly dwelling on worst-case scenarios, overestimating threats, or engaging in self-criticism can trigger and fuel anxiety. Learn more about anxiety triggers.

Cognitive Distortions: These are inaccurate or unhelpful thinking patterns that make us more vulnerable to anxiety.

Brain Chemistry & Genetics

Imbalances in neurotransmitters (serotonin, GABA, norepinephrine).

Amygdala: This small, almond-shaped structure acts as the brain’s alarm system, processing emotions, particularly fear and anxiety. When it perceives a threat (real or imagined), it triggers the stress response, preparing the body to fight or flee. Learn about the role of the amygdala in anxiety.

Prefrontal Cortex: This area is responsible for decision-making, planning, and impulse control. It helps regulate the amygdala’s response and assess whether a perceived threat is real or not.

Neurotransmitters: These are chemical messengers that transmit signals between brain cells. Imbalances in neurotransmitters like serotonin, GABA, norepinephrine, and dopamine can contribute to anxiety.

Family history of anxiety can increase your vulnerability.

Life Experiences

Traumas, chronic stress, sudden life changes.

Modern stressors (e.g., workload, finances, social media pressures).

Environmental & Lifestyle Factors

Poor sleep, high caffeine or alcohol intake, inadequate stress management.

How to Know if You Need Professional Help

A stepped-care approach is often used:

- Mild Anxiety: Try self-help (books, online resources) and lifestyle changes first.

- Persistent or Worsening Anxiety: Consider therapy (e.g., CBT) and/or medication.

- Severe Anxiety: May require specialized or intensive treatment, combining multiple modalities and professional oversight.

If you follow a stepped-care approach, you may not need treatment by a psychologist, as you can start with self-help. I would have used a stepped care approach when working in the UK, and see that the HSE adopts the same. The idea of this type of working is to do with resources, efficiency and cost, for example, it does not make sense to use all the resources of a mental health team to help someone with mild anxiety, self- help may suffice. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE for short) gives guidance on a Stepped Care Approach, which suggests

- Assessment, education and discussion of treatment options

- This could be a meeting with your local GP, who diagnoses anxiety or refers you to a psychologist for psychological assessment. Your GP or mental health consultation will explain anxiety to you and recommend treatment options, which may start with self-help.

- Self-Help

- This can be self-help that you undertake alone on in groups

- CBT with a Psychologist

- If self-help does not work for you, you might be referred to someone like myself, a psychologist for CBT.

- Highly Specialised Treatment

- When I worked in the UK I was part of a highly specialised multi-disciplinary team where people would be seen by psychologist, have psychiatrists to monitor medication and could also involve in-patient care.

If anxiety interferes with your work, relationships, or overall well-being despite self-help efforts, I recommend reading how to get help for anxiety in Ireland.

Diagnosis

If you suspect you might have an anxiety disorder, it is essential to meet with a licensed mental health professional; a psychologist or psychiatrist can undertake an assessment and tell you not only if you have anxiety, but what type you have.

The clinician will use a tool called the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). According to the DSM, the criteria for anxiety include the following;

- excessive anxiety and worry most days about many things for at least six months

- difficulty controlling your worry

- the appearance of three of the following six symptoms: restlessness, fatigue, irritability, muscle tension, sleep disturbance, and difficulty concentrating

- symptoms significantly interfering with your life

- symptoms not being caused by the direct psychological effects of medications or medical conditions

- symptoms aren’t due to another mental disorder (e.g. anxiety about oncoming panic attacks with panic disorder, anxiety due to a social condition, etc.)

How to deal with anxiety right now

If you are feeling anxious right in this very moment, the remainder of this article includes videos I made to help you with guided relaxation. They are only short-term strategies and do not replace meeting with a mental health professional for assessment and treatment.

If you are feeling anxious right now, the following brief videos will help you manage your current anxiety.

Controlled breathing

The following video will help you to control your breathing.

7-11 breathing

“Dr. Elaine Ryan is a Dublin-based psychologist with a proven track record in treating anxiety disorders. With over 20 years of experience, she offers compassionate and effective therapy to help individuals overcome their challenges. To schedule an appointment or learn more about Dr. Ryan’s services, please feel free to contact the clinic.”

References

Ekman P. Basic Emotions. Handbook of Cognition and Emotion. 2005:45-60. doi:10.1002/0470013494.ch3

Hockenbury, D. and Hockenbury, S.E. (2007). Discovering Psychology.New York: Worth Publishers.

Vora, E. (2022) The anatomy of anxiety. Orion Spring